Solvency II is a worn out subject for many in the insurance industry. After over 10 years of in depth discussions and testing, the current target date of 01/01/2016 remains uncertain until the vexed issue of how long term guarantees in life business is resolved.

The aim of the proposed Solvency II framework is to ensure that (re)insurers are financially sound and can withstand adverse events in order to protect policy holders and the stability of the financial system as a whole. Somewhere along the long road to where we are now, the solvency capital requirement (SCR) in Solvency II to achieve that aim was set at an amount of economic capital corresponding to a ruin probability of 0.5% (Value at Risk or VaR of 99.5%) and a one year time horizon.

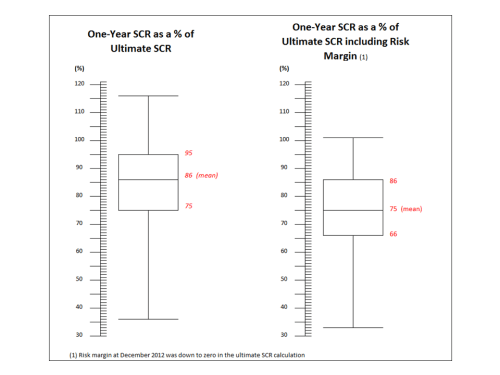

Many global reinsurers and insurers now publish outputs from their internal models in annual reports and investor presentations, most of which are set at one year 99.5% VaR or an equivalent level. Lloyds’ of London however is somewhat different. Although the whole Lloyds’ market is subject to the one year Solvency II calibration on an aggregate basis, each of the Syndicates operating in Lloyds’ have a solvency requirement based upon a 99.5% VaR on a “to ultimate” basis. In effect, Syndicates must hold additional capital to that mandated under Solvency II to take into account the variability in their results on an ultimate basis. I recently came across an interesting presentation from Lloyds’ on the difference in the SCR requirement between a one year and an ultimate basis (which requires on average a third more capital!), as the exhibit below reproducing a slide from the presentation shows.

click to enlarge

Although this aspect of Lloyds’ of London capital requirements has not been directly referenced in recent reports, their conservative approach does reflect the way the market is now run and could likely be a factor behind recent press speculation on a possible upgrade for the market to AA. Such an upgrade would be a massive competitive plus for Lloyds’.