I expect that next week’s reinsurance jamboree in Monte Carlo will be full of talk of innovative and technology streaming-lining business models (as per this post on AI and insurance). This recent article from the FT is just one example of claims that technology like blockchain can reduce costs by 30%. The article highlights questions about whether insurers are prepared to give up ownership of data, arguably their competitive advantage, if the technology is really to be scaled up in the sector.

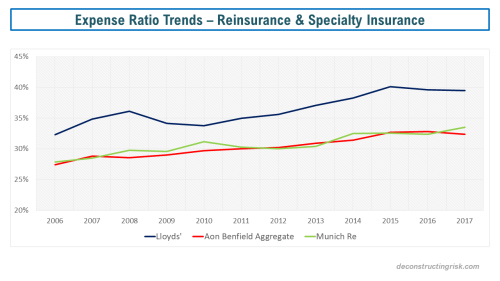

As a reminder of the reinsurance sector’s cost issues, as per this post on Lloyds’, the graph below illustrates the trend across Lloyds’, the Aon Benfield Aggregate portfolio, and Munich’s P&C reinsurance business.

Until the sector gets serious about cutting costs, such as overpaid executives on luxury islands or expensive cities and antiquated business practises such as holding get togethers in places like Monte Carlo, I suspect expenses will remain an issue. In their July review, Willis stated that a “number of traditional carriers are well advanced in their plans to reduce their costs, including difficult decisions around headcount” and that “in addition to cost savings, the more proactively managed carriers are applying far greater rigor in examining the profitability of every line of business they are accepting”. Willis highlighted the potential difficulties for the vastly inefficient MGA business that many have been so actively pursuing. As an example of the type of guff executives will trot out next week, Swiss Re CEO, Christian Mumenthaler, said “we remain convinced that technology will fundamentally change the re/insurance value chain”, likely speaking from some flash office block in one of the most expensive cities in the world!

On market conditions, there was positive developments on reinsurance pricing at the January renewals after the 2017 losses with underlying insurance rates improving, as illustrated by the Marsh composite commercial rate index (example from US below).

However, commentators have been getting ever more pessimistic as the year progresses, particularly after the mid-year renewals. Deutsche Bank recently called the reinsurance pricing outlook “very bleak”. A.M. Best stated that “the new normal for reinsurers appears to be one with returns that are less impressive and underwriting and fee income becoming a larger contributor to profits” and predicts, assuming a normal large loss level, an 8% ROE for 2018 for the sector. Willis, in their H1 report, puts the sectors ROE at 7.7% for H1 2018. S&P, in the latest report that is part of their Global Highlights series, also expects a ROE return for 2018 around 6% to 8% and estimates that “reinsurers are likely to barely cover their cost of capital in 2018 and 2019”.

S&P does question why “the market values the industry at a premium to book value today (on average at 1.24x at year-end 2017), and at near historical highs, given the challenges” and believes that potential capital returns, M&A and interest rate rises are all behind elevated valuations. The recent Apollo PE deal for Aspen at 1.12 times book seems a large way off other recent multiples, as per this post, but Aspen has had performance issues. Still its interesting that no other insurer was tempted to have a go at Aspen with the obvious synergies that such a deal could have achieved. There is only a relatively small number of high quality players left for the M&A game and they will not be cheap!

As you are likely aware, I have been vocal on the impact the ILS sector has had in recent years (most recently here and here). With so-called alternative capital (at what size does it stop being alternative!) now at the $95 billion-mark according to Aon, A.M. Best makes the obvious point that “any hope for near-term improvement in the market is directly correlated to the current level of excess capacity in the overall market today, which is being compounded by the continued inflow of alternative capacity”. Insurers and reinsurers are not only increasing their usage of ILS in portfolio optimisation but are also heavily participating in the sector. The recent purchase by Markel of the industry leading and oldest ILS fund Nephila is an interesting development as Markel already had an ILS platform and is generally not prone to overpaying.

I did find this comment from Bob Swarup of Camdor in a recent Clear Path report on ILS particularly telling – “As an asset class matures it inevitably creates its own cycle and beta. At this point you expect fees to decline both as a function of the benefits of scale but also as it becomes more understood, less of it becomes alpha and more of it becomes beta” and “I do feel that the fees are most definitely too high right now and to a large extent this is because people are trying to treat this as an alternative asset class whereas it is large enough now to be part of the general mix”. Given the still relatively small size of the ILS sector, it’s difficult for ILS managers to demonstrate true alpha at scale (unless they are taking crazy leveraged bets!) and therefore pressure on current fees will become a feature.

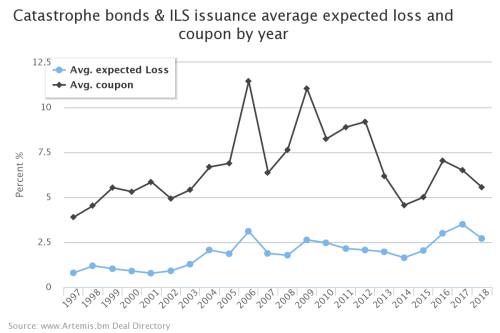

A.M. Best articulated my views on ILS succinctly as follows: “The uncorrelated nature of the industry to traditional investments does appear to have value—so long as the overall risk-adjusted return remains appropriate”. The graph below from artemis.bm shows the latest differential between returns and expected cost across the portfolio they monitor.

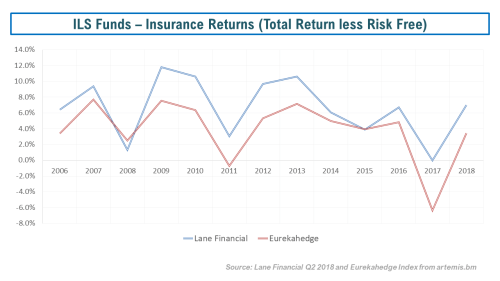

In terms of the returns from ILS funds, the graph below shows the underlying trend (with 2018 results assuming no abnormal catastrophic activity) of insurance only returns from indices calculated by Lane Financial (here) and Eurekahedge (here). Are recent 5 year average returns of between 500 and 250 basis points excess risk free enough to compensation for the risk of a relatively concentrated portfolio? Some think so. I don’t.

Whether reinsurers and specialty insurers will be able to maintain superior (albeit just above CoC) recent returns over ILS, as illustrated in this post, through arbitrating lower return ILS capital or whether their bloated costs structures will catch them out will be a fascinating game to watch over the coming years. I found a section of a recent S&P report, part of their Global Highlights series, on cat exposures in the sector, amusing. It stated that in 2017 “the reinsurance industry recorded an aggregate loss that was assessed as likely to be incurred less than once in 20 years” whilst “this was the third time this had happened in less than 20 years“.

So, all in all, the story is depressingly familiar for the sector. The new normal, as so many commentators have recently called it, amounts to overcapacity, weak pricing power, bloated cost structures, and optimistic valuations. Let’s see if anybody has anything new or interesting to say in Monte Carlo next week.

As always, let’s hope there is minimal human damage from any hurricanes such as the developing Hurricane Florence or other catastrophic events in 2018.