My father was not a man of many words, but when he spoke, he generally made a lot of sense. Somebody could not be called anything more derogatory by my father than to be called a clown, a term he generally used often when watching politicians on the TV. He would have had absolutely no time for the current US president, a clown of the highest order in my father’s meaning of the word. Notwithstanding the loss of life from the Capitol Hill rioting, the pantomime that played out on the 6th of January was pure theatre and showed the vacuous inevitable end destination of Trump’s narcissism (and hopefully of Trumpism). Rednecks roaming around capitol building with confederate flags and wearing silly costumes feels like a fitting end. I thought it would be months, if not years, before the doubtless shenanigans that Trump has been up to over the past 4 years (and before that, of course) would be made public in all its glory and before a large proportion of the otherwise sensible 74 million Americans who voted for him would finally see him for the “very flawed human being”, in his ex-Chief of Staff John Kelly’s wonderfully diplomatic words, that he is. My father had another word for him. There are too many issues to be dealt with that are more important than the man child who will, after this week, be a (hopefully!) much-diminished and irrelevant force.

Most people are happy to see the back of 2020 and there is little that I can add to that sentiment. Like others, I have avoided any year end round ups as it all seems too raw. My family and I have been blessed to not been adversely impacted health-wise by Covid-19 during the year. The horrible global death toll from the virus reached the grim milestone of 2 million with some pessimistic projections of the final toll at double that figure, even if mass vaccinations result in the utopian herd immunity (optimistic projections for the developed world to reach such a state by this time next year with the rest of the world taking another 12 months). It seems likely that the public health situation will get worse before it gets better.

Reaching the milestone age of 21 symbolizes the entry into adulthood, an age of maturity, and not just in relation to the legal procurement of alcohol in some countries! Maturity and long-term thinking in addressing the challenges of the coming year, including likely bottlenecks in vaccine rollouts and the rebuilding of multilateral cooperation, should replace the narrow nationalist thinking of the Trump and Brexit eras. God willing, the biblical symbolism of 21 representing the “great wickedness of rebellion and sin” will not be backdrop for the post-Covid era!

In a widely optimistic thought along the lines of rebellion and sin but without the wickedness, the post-Covid era could be characterised by a radical shift in societal norms, akin to the 60’s, where youth culture demands that the challenges of our day, specifically climate change and income equality, are addressed urgently. Combining technology with a passion for action and upsetting lifestyle norms could instigate real change. A new countercultural movement, with its own hedonistic soundtrack, would also be nice after all the introspection of lockdowns! 2020 has taught us that rapid social change can take place and we can adapt to uncertainty if we are pushed.

So back to the realities of 2021! I read recently that those of us lucky enough to be able to continue working relatively unperturbed from home during Covid having been working on average an hour a day extra and that is consistent with my experience (and thus my lack of posts on this blog!). Overcoming the challenges of the current Covid operating environment, such as avoiding the development of splintered or siloed cultures, whilst maintaining a collective corporate spirit will likely be a much-discussed topic in 2021. As the social capital of pre-Covid working networks is eroded by time and Covid fatigue, moving to a new hybrid work/office model in our new distributed working environment, whilst minimising people and talent risk, will create both challenges and opportunities for leaders and managers of differing skillsets.

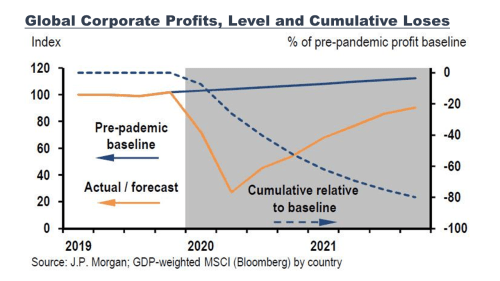

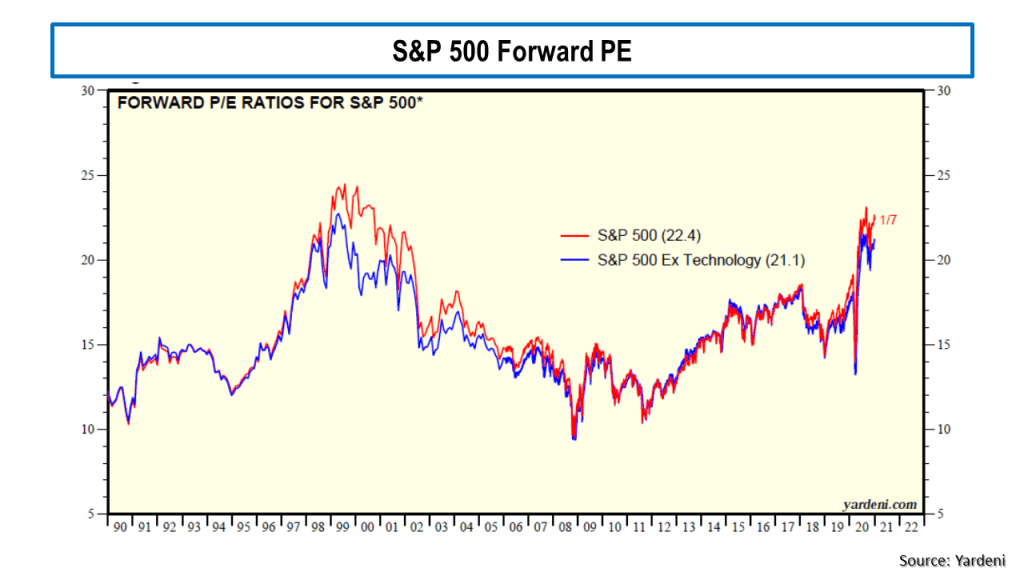

One of my biggest concerns for 2021 is the financial markets. The macabre sight of stock markets hitting highs as the pandemic worsened is surely one of paradoxes of 2020. The S&P500 is currently trading at a forward PE ratio of over 22 as the graphic below shows.

In November, the oft debated (see this post as an example) cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio for the S&P 500 hit 33, just above the level it was at in September 1929, the month before the crash that preceded the Great Depression! CAPE has only been higher twice in history than it is now, in the late 1920’s and the early 2000’s. Apple (AAPL) is currently valued at a forward PE of over 30 (based upon its 2022 earnings estimates), trading well above the sub $100 level I pitched as fair value earlier this year (in this post). Tesla is often cited as the poster child for crazy valuations. I like to look at the newly public Airbnb (ABNB) for my example, a firm that depends upon cross border travel for its core business, which has lost $1 billion on revenue of $3.6 billion over the last 12 months (revenue down from $4.8 billion in 2019) and is now valued at $100 billion or a multiple of over 27 times sales! The market seems to be solely focussed on the upward leg and ignoring the downward leg of the so-called K shaped (bifurcated) recovery, even though small business in the US generate 44% of US economic activity. The forward PE on the Russell 2000 is above 30. In classic bubble style, speculative assets like bitcoin reached all-time highs. The latest sign is that much shorted stocks are being targeted in short squeeze trades.

This NYT article, aptly named “Why Markets Boomed in a Year of Human Misery” offers one of the clearest explanations for the market euphoria, namely that the “Fed played a big part in engineering the stabilization of the markets in March and April, but the rally since then probably reflects these broader dynamics around savings”. The broader dynamics referred to are the NPIA statistics from March to November. The article highlights that fiscal action taken to support US households through Covid support has resulted in salaries and wages only being marginally down on the prior year, despite widespread lockdowns, whilst spending has fallen. This combination pushed the US savings rate through the roof, over $1.5 trillion higher that the March to November period in 2019.

The arguments about a bubble have been rehashed of late and here are some examples:

- In November, Robert Shiller (of CAPE fame) co-authored an article which stated “many have been puzzled that the world’s stock markets haven’t collapsed in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic downturn it has wrought. But with interest rates low and likely to stay there, equities will continue to look attractive, particularly when compared to bonds.”

- The great Martin Wolf of the FT asked (in this article) “Will these structural, decades-long trends towards ultra-low real interest rates reverse? The answer has to be that real interest rates are more likely to rise than fall still further. If so, long-term bonds will be a terrible investment. But it also depends on why real interest rates rise. If they were to do so as a product of higher investment and faster growth, strong corporate earnings might offset the impact of the higher real interest rates on stock prices. If, however, savings rates were to fall, perhaps because of ageing, there would be no such offset, and stock prices might become significantly overvalued.”

- The ever-pessimistic John Hussman responded in this market commentary that “when people say that extreme stock market valuations are “justified” by interest rates, what they’re actually saying is that it’s “reasonable” for investors to price the stock market for long-term returns of nearly zero, because bonds are also priced for long-term returns of nearly zero. I know that’s not what you hear, but it’s precisely what’s being said.”

- And the equally sunny veteran market player Jeremy Grantham opened his latest investor letter (the wonderfully titled “Waiting for the last dance”) thus: “The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully-fledged epic bubble. Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases, frenzied issuance, and hysterically speculative investor behavior, I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Sea bubble, 1929, and 2000.”

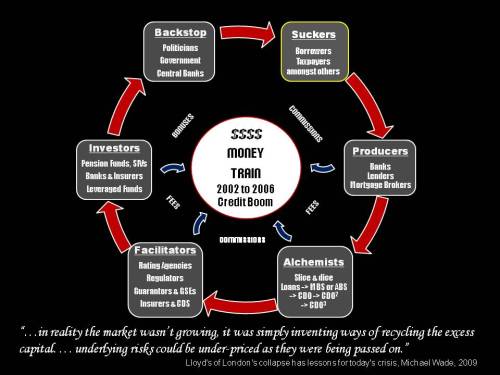

Grantham points out that the necessary monetary and fiscal reaction to the pandemic has created heighten moral hazard – “The longer the moral hazard runs, and you have this implied guarantee, the more the market feels it can take more risk. So it takes more risk and builds yet more debt. We’ve counted too much on the permanence and the stability of low rates and low inflation. At the end of this great cycle of stability, all the market has to do is cough. If bond yields mean-revert even partially, they will be caught high and dry.”

I particularly liked Graham’s summary of the past 20 odd years of monetary policy – “All bubbles end with near universal acceptance that the current one will not end yet…because. Because in 1929 the economy had clicked into “a permanently high plateau”; because Greenspan’s Fed in 2000 was predicting an enduring improvement in productivity and was pledging its loyalty (or moral hazard) to the stock market; because Bernanke believed in 2006 that “U.S. house prices merely reflect a strong U.S. economy” as he perpetuated the moral hazard: if you win you’re on your own, but if you lose you can count on our support. Yellen, and now Powell, maintained this approach. All three of Powell’s predecessors claimed that the asset prices they helped inflate in turn aided the economy through the wealth effect.”

There is no doubt in my mind that we are in an asset price bubble currently, notwithstanding the fact that it is likely to continue for some time yet. Although not quite at the level of Joe Kennedy hearing the shoeshine boy talk about his equity positions, I have been struck by the attitude of late of my more junior workmates when they optimistically talk about their equity and bitcoin investment gains. It’s more akin to a level of the mobsters’ spouses trading internet stock ideas in the Sopranos! The TINA trade on steroids or the TINA USP as in “there is no alternative, Uncle Sam’s paying!”.

There is little doubt that extraordinary action, both monetary and fiscal, was needed to counteract the impact of the pandemic. In the words of Andy Haldane, chief economist of the Bank of England, “now is not the time for the economics of Chicken Licken”. It is the sheer scale and reliance on government intervention into markets that surely is unhealthy in the medium to longer term. Central banks now act as market makers, distorting market dynamics such that continued newly created money chases an ever-shrinking pool of investable assets. William White, formerly of the BIS, recently commented that monetary policy has been asymmetric whereby Central banks have put a floor under markets in crises but failed to put a cap on prices in bubbles.

Fiscal stimulus has exploded the world’s government debt stocks. Fitch estimate that global government debt increased by about $10 trillion in 2020 to $78 trillion, equivalent to 94% of world GDP. The previous $10 trillion tranche took seven years to build, from 2012 to 2019. The most immediate impact has been on emerging market debt with sovereign downgrades prevalent. Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist at the IMF, warned that “this is going to be a rocky road”. High debt levels can only be contained in the future by austerity or inflation, neither of which are pleasant and both of which would further compound high levels of inequality across the world. Covid has laid bare the destructive impact of inequality and anything that will increase inequality will inevitably impact social stability (eh, more populism anyone?). We have, of course been here before, living through it over the past 13 years, but this time the volume is up to 11.

Two other issues that will keep us occupied in 2021 are climate change and cyber risks. 2020 has recently been declared one of the hottest on record. Despite the estimated 7% fall in CO2 emissions in 2020 due to Covid lockdowns, we are still, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres highlighted this week, “headed for a catastrophic temperature rise of 3 to 5 degrees Celsius this century”. David Attenborough’s new TV programme “A Perfect Planet” illustrates the impact that the current temperature rises just above 1 degree are having right now on the delicate balance of nature. The COP26 summit in November this year must be an event where real leadership is shown if this fragile planet of ours has any hope for the long term. The other issue which will likely get more attention in 2021 is the successful cyber intrusions using Solarwinds that the Russians pulled off in 2020. An anonymous senior US official recently stated that “the current way we are doing cybersecurity is broken and for anyone to say otherwise is mistaken”.

So, 2021 promises to be another significant year, one of more change but, at least it will be without the clown (hopefully). I, for one, will eagerly wait for any signs of that new countercultural movement to take hold, whilst listening out for that hedonistic soundtrack!

A happy and healthy new year to all.