The release of the synthesis reports by the IPCC – in summary, short and long form – earlier this month has helped to keep the climate change debate alive. I have posted (here, here, and here) on the IPCC’s 5th assessment previously. The IPCC should be applauded for trying to present their findings in different formats targeted at different audiences. Statements such as the following cannot be clearer:

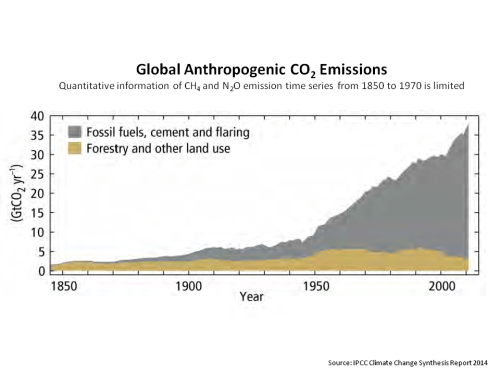

“Anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased since the pre-industrial era, driven largely by economic and population growth, and are now higher than ever. This has led to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years. Their effects, together with those of other anthropogenic drivers, have been detected throughout the climate system and are extremely likely to have been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.”

The reports also try to outline a framework to manage the risk, as per the statement below.

“Adaptation and mitigation are complementary strategies for reducing and managing the risks of climate change. Substantial emissions reductions over the next few decades can reduce climate risks in the 21st century and beyond, increase prospects for effective adaptation, reduce the costs and challenges of mitigation in the longer term, and contribute to climate-resilient pathways for sustainable development.”

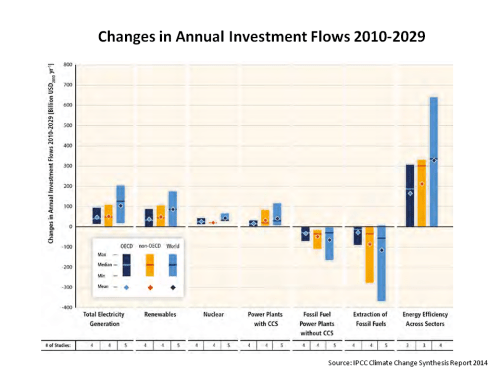

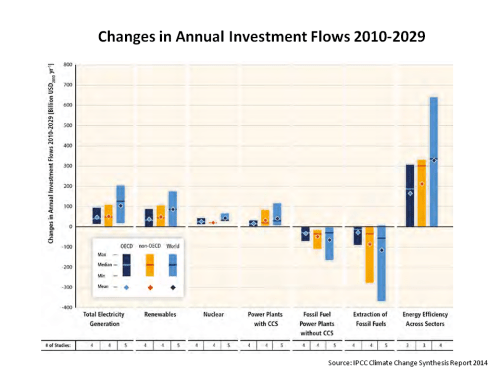

The IPCC estimate the costs of adaptation and mitigation of keeping climate warming below the critical 2oC inflection level at a loss of global consumption of 1%-4% in 2030 or 3%-11% in 2100. Whilst acknowledging the uncertainty in their estimates, the IPCC also provide some estimates of the investment changes needed for each of the main GHG emitting sectors involved, as the graph reproduced below shows.

click to enlarge

The real question is whether this IPCC report will be any more successful that previous reports at instigating real action. For example, is the agreement reached today by China and the US for real or just a nice photo opportunity for Presidents Obama and Xi?

In today’s FT Martin Wolf has a rousing piece on the subject where he summaries the laissez-faire forces justifying inertia on climate change action as using the costs argument and the (freely acknowledged) uncertainties behind the science. Wolf argues that “the ethical response is that we are the beneficiaries of the efforts of our ancestors to leave a better world than the one they inherited” but concludes that such an obligation is unlikely to overcome the inertia prevalent today.

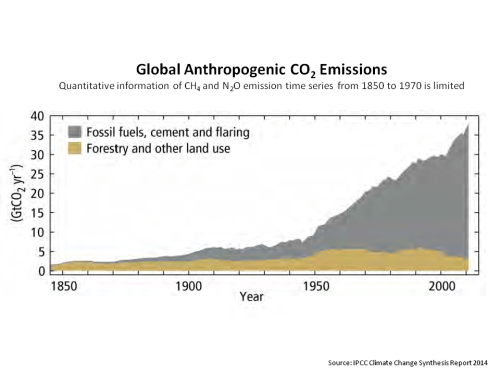

I, maybe naively, hope for better. As Wolf points out, the costs estimated in the reports, although daunting, are less than that experienced in the developed world from the financial crisis. The costs don’t take into account any economic benefits that a low carbon economy may result in. Notwithstanding this, the scale of the task in changing the trajectory of the global economy is illustrated by one of graphs from the report, as reproduced below.

click to enlarge

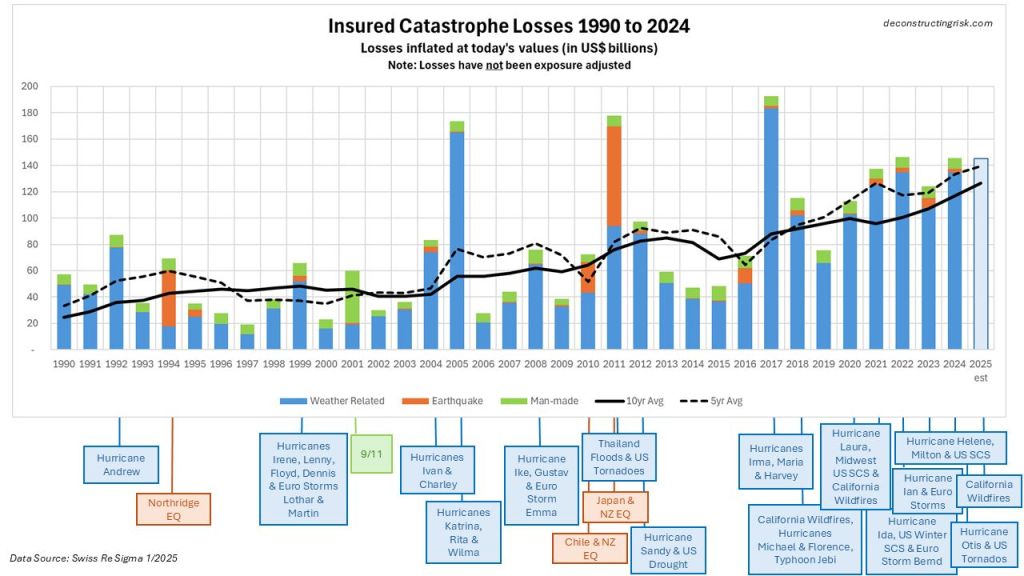

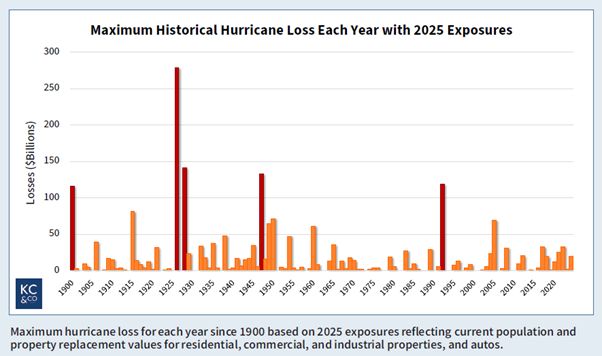

Although the insurance sector has a minimal impact on the debate, it is interesting to see that the UK’s Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) recently issued a survey to the sector asking for responses on what the regulatory approach should be to climate change.

Many industry players, such as Lloyds’ of London, have been pro-active in stimulating debate on climate change. In May, Lloyds issued a report entitled “Catastrophic Modelling and Climate Change” with contributions from industry. In the piece from Paul Wilson of RMS in the Lloyds report, they concluded that “the influence of trends in sea surface temperatures (from climate change) are shown to be a small contributor to frequency adjustments as represented in RMS medium-term forecast” but that “the impact of changes in sea-level are shown to be more significant, with changes in Superstorm Sandy’s modelled surge losses due to sea-level rise at the Battery over the past 50-years equating to approximately a 30% increase in the ground-up surge losses from Sandy’s in New York.“ In relation to US thunderstorms, another piece in the Lloyds report from Ionna Dima and Shane Latchman of AIR, concludes that “an increase in severe thunderstorm losses cannot readily be attributed to climate change. Certainly no individual season, such as was seen in 2011, can be blamed on climate change.“

The uncertainties associated with the estimates in the IPCC reports are well documented (I have posted on this before here and here). The Lighthill Risk Network also has a nice report on climate model uncertainty which concludes that “understanding how climate models work, are developed, and projection uncertainty should also improve climate change resilience for society.” The report highlights the need for expanding geological data sets beyond short durations of decades and centuries which we currently base many of our climate models on.

However, as Wolf says in his FT article, we must not confuse the uncertainty of outcomes with the certainty of no outcomes. On the day that man has put a robot on a comet, let’s hope the IPCC latest assessment results in an evolution of the debate and real action on the complex issue of climate change.

Follow-on comment: Oh dear the outcome of the Philae lander may not be a good omen!!!