Every investor knows the feeling of wondering what to do when a stock they have invested in falls unexpectedly in value. Although some may not be aware of the term “disposition effect” in behavioural economics, it reflects the widely observed tendency of investors to ride losses and lock in gains (a previous post touched on more behaviour economic concepts). I have been guilty in the past of just such a tendency, all too often I’m afraid! Bitter experience, maturity and the advice of many successful professional investors has caused me to now try to proactively act against such instincts. [On the latter point, the books of Jack Schwager and Steven Drobny with wide ranging professional investor interviews are must reads.]

Averaging down when a stock you hold falls, particularly when there is no obvious explanation, is another strategy that rarely ends well. Instead of looking at the situation as an opportunity to buy more of a stock at a reduced price, I now question why I would invest more in a situation that I have clearly misread. I only allow myself to consider averaging down where I clearly understand the reason behind any decrease and where the market itself has reduced (for the sector or as a whole). Experience has taught me that focusing on reducing the losers is critical to longer term success. Paul Tudor Jones put it well when he said: “I am always thinking about losing money as opposed to making money”.

This brings me to the case in point of my investment in Trinity Biotech (TRIB). I first posted about TRIB in September 2013 (here) where I looked at the history of the firm and concluded that “TRIB is a quality company with hard won experiences and an exciting product pipeline” but “it’s a pity about the frothy valuation” (the stock was trading around $19 at the time). The exciting pipeline included autoimmune products from the Immco acquisition, the launch of the new Premier diabetes instruments from the Primus acquisition, and the blockbuster potential of Troponin point-of-care cardiac tests going through FDA trials from the Fiomi deal.

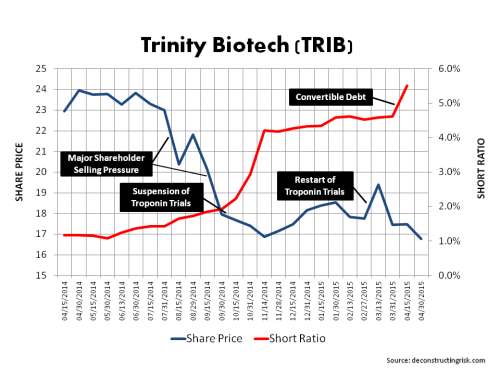

Almost immediately after the September 2013 post, the stock climbed to a high of over $27 in Q1 2014, amidst some volatility. Fidelity built its position to over 12% during this time (I don’t know if that was on its own behalf or for an investor) before proceeding to dump its position over the remainder of 2014. This may simply have been a build up and a subsequent unwinding of an inverse tax play which was in, and then out, of vogue at the time. The rise of the stock after my over-valued call may have had a subconscious impact on my future actions.

By August 2014, the stock traded around the low $20s after results showed a slightly reduced EPS on lower Lyme sales and reduced gross margins on higher Premier instrument sales and lagging higher margin reagent sales. Thinking that the selling pressure had stopped after a drop by TRIB from the high $20 level to the low $20s, I revised my assessment (here) and established an initial position in TRIB around $21 on the basis of a pick-up in operating results from the acquisitions in future quarters plus the $8-$10 a share embedded option estimated by analysts on a successful outcome of the Troponin trials. As a follow-on post in October admitted, my timing in August was way off as the stock continued its downward path through September and October.

With the announcement of a suspension of the FDA Troponin trials in late October due to unreliable chemical agent supplied by a 3rd party, the stock headed towards $16 at the end of October. Despite my public admission of mistiming on TRIB in the October post and my proclamations of discipline in the introduction to this post, I made a classic investing mistake at this point: I did nothing. As the trading psychologist Dr Van Tharp put it: “a common decision that people make under stress is not to decide”. After a period of indecision, some positive news on a CLIA waiver of rapid syphilis test in December combined with the strength of the dollar cut my losses on paper so I eventually sold half my position at a small loss at the end of January. I would like to claim this was due to my disciplined approach but, in reality, it was primarily due to luck given the dollar move.

Further positive news on the resumption of the Troponin trials in February, despite pushing out the timing of any FDA approval, was damped by disappointing Q4 results with lacklustre operating results (GM reduction, revenue pressures on legacy products). The continued rise in the dollar again cushioned my paper loss. It wasn’t until TRIB announced and closed a $115 million exchangeable debt offering in April that I started to get really concerned (my thoughts on convertible debt are in this post) about the impact such debt can have on shareholder value. I decided to wait until the Q1 call at the end of April to see what TRIB’s rationale was for the debt issuance (both the timing and the debt type). I was dissatisfied with the firm’s explanation on the use of funds (no M&A target has been yet identified) and when TRIB traded sharply down last week, I eventually acted and sold all of my remaining position around $16 per share, an approximate 15% loss in € terms after the benefits on the dollar strength. The graph below illustrates the events of the recent past.

My experience with TRIB only re-enforces the need to be disciplined in cutting losses early. On the positive side, I did scale into the position (I only initially invested a third of my allocation) and avoided the pitfall of averaging down. Joe Vidich of Manalapan Oracle Capital Management puts it well by highlighting the need for strong risk management in relation to the importance of position sizing and scaling into and out of positions when he said “the idea is don’t try to be 100% right”. Although my inaction was tempered by the dollar strength, the reality is that I should have cut my losses at the time of the October post. Eventually, I forced myself into action by strict portfolio management when faced with a market currently stretched valuation wise, as my previous post hightlights.

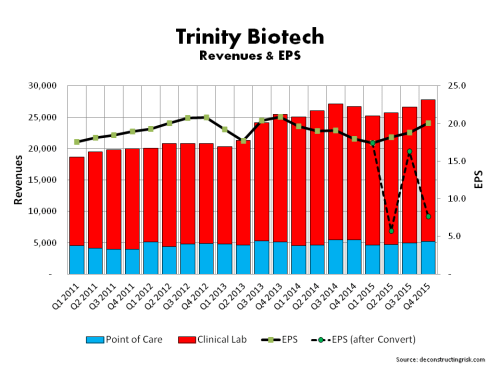

As for TRIB, I can now look at its development from a detached perspective without the emotional baggage of trying to justify an investment mistake. The analysts have being progressively downgrading their EPS estimates over recent months with the average EPS estimates now at $0.16 and $0.69 for Q2 and FY2015 respectively. My estimates (excluding and including the P&L cost of the new debt of $6.3 million per year, as per the management estimate on the Q1 call) are in the graph below.

In terms of the prospects for TRIB in the short term, I am concerned about the lack of progress on the operational results from the acquisitions of recent years and the risks (timing and costs) associated with the Troponin approval. I also do not believe management should be looking at further M&A until they address the current issues (unless they have a compelling target). The cost of the debt will negatively impact EPS in 2015. One cynical explanation for the timing on the debt issuance is that management need to find new revenues to counter weakness in legacy products that can no longer be ignored. Longer term TRIB may have a positive future, it may even climb from last week’s low over the coming weeks. That’s not my concern anymore, I am much happier to take my loss and watch it from the side-lines for now.

Ray Dalio of Brightwater has consistently stressed the need to learn from investing mistakes: “whilst most others seem to believe that mistakes are bad things, I believe mistakes are good things because I believe that most learning comes via making mistakes and reflecting on them”. This post is my reflection on my timing on TRIB, my inaction in the face of a falling position, and my current perspective on TRIB as an investment (now hopefully free of any emotive bias!).