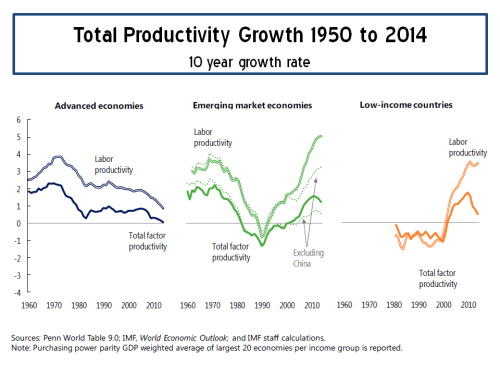

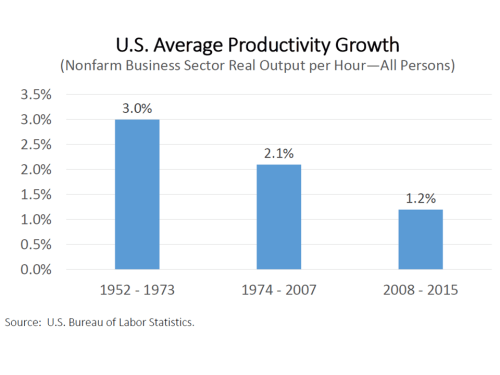

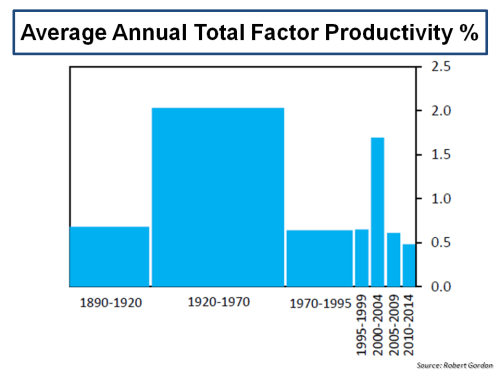

The IMF has sponsored another paper from staffers on the global productivity slowdown, with the catchy title “Gone with the Headwinds”. The paper reiterates many of the arguments concerning advanced economies referenced in this post, such as total factor productivity (TFP) hysteresis due to the boom-bust financial cycle and resulting capital misallocation, “an adverse feedback loop of weak aggregate demand, investment, and capital-embodied technological change”, elevated economic and policy uncertainty.

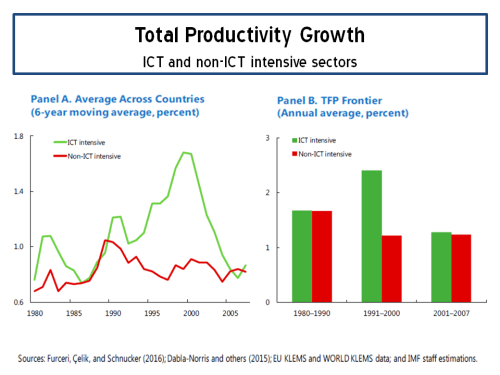

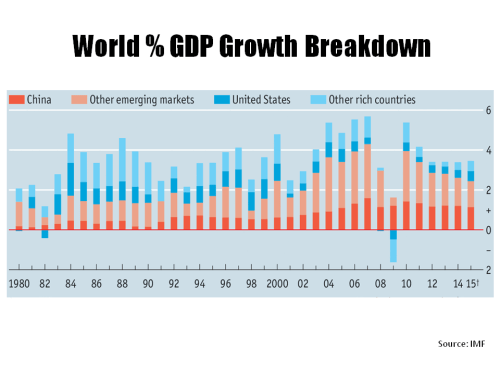

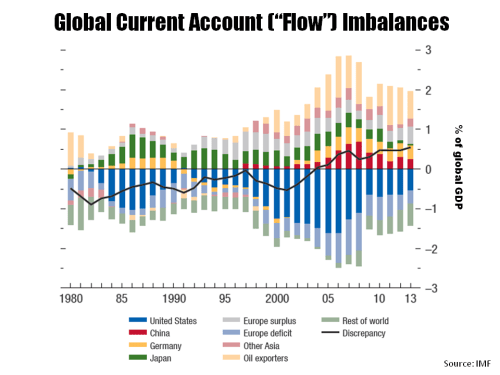

Also cited are structural headwinds including a waning information and communication technology (ICT) boom, an aging workforce, slower human capital accumulation, and slowing global trade integration (including the maturing of China’s integration into world trade). An exhibit on the ICT trends from the report is reproduced below.

The report highlights short term remedies such as boosting private sector demand, efficient spending on infrastructure, strengthening balance sheets, and reducing economic policy uncertainty. Longer term remedies cited include policies to boost technological progress, policies to mitigate the effects of aging, policies to encourage migration, advancing an open global trade system, exploiting policy synergies, structural reforms, raising the quantity and quality of human capital.

Now, how many of these remedies are likely to be pursued in the current populist political environment? Although Trump has shown signs recently of doing the opposite to what he fought the election on, overall it does look like we are merrily going down a policy dead-end for the next few years in important advanced economies. Hopefully the policy dead-end will be principally confined to the US and they wouldn’t take too long in figuring out the silliness of the current journey and the need to get back to trying to deal with the big issues intelligently. Then again….