My initial reaction, from a shareholder view-point, when a firm issues a convertible bond is negative and I suspect that many other investors feel the same. My experience as a shareholder of firms that relied on such hybrid instruments has been varied in the past. Whether it’s a sign that a growing firm has limited options and may have put the shareholder at the mercy of some manipulative financier, or the prospect that arbitrage quants will randomly buy or sell the stock at the whim of some dynamic hedging model chasing the “greeks”, my initial reaction is one of discomfort at the uncertainty of how, by whom, and when my shareholding may be diluted.

In today’s low risk premia environment, it’s interesting to see a pick-up in convertible issuances and, in the on-going search for yield environment, investors are again keen on foregoing some coupon for the upside which the embedded call option that convertibles may offer. Names like Tesla, AOL, RedHat, Priceline and Twitter have all been active in recent times with conversion premiums averaging over 30%. The following graph shows the pick-up in issuances according to UBS.

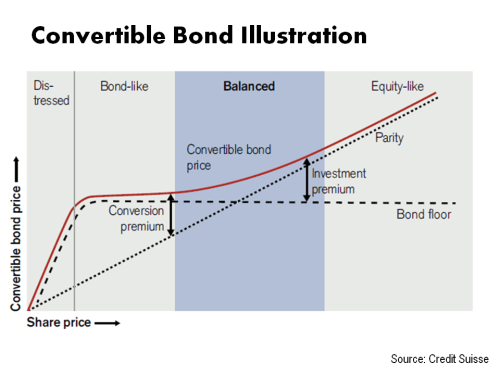

Convertible bonds have been around since the days of the railroad boom in the US and, in theory, combining the certainty of a regular corporate bond with an equity call option which offers the issuer a source of low debt cost at a acceptable dilution rate to shareholders whilst offering an investor the relative safety of a bond with a potential for equity upside. The following graphic illustrates the return characteristics.

The problem for the asset class in the recent past came when the masters of the universe embraced convertible arbitrage strategies of long/short the debt/equity combined with heavy doses of leverage and no risk capital. The holy grail of an asymmetric trade without any risk was assumed to be at hand [and why not, given their preordained godness…or whatever…]! Despite the warning shot to the strategy that debt and equity pricing can diverge when Kirk Kerborian’s increased his stake in General Motors in 2005 just after the debt was downgraded, many convertible arb hedge funds continued to operate at leverage multiples of well in excess of 4.

The 2008 financial crisis and the unwinding of dubious lending practises to facilitate hedge fund leverage, such as the beautifully named rehypothecation lending by banks and brokers (unfortunately the actual explanation sounds more like a ponzi scheme), caused the arbitrage crash not only across convertibles but across many other asset classes mixed up in so called relative value strategies. This 2010 paper, entitled “Arbitrage Crashes and the Speed of Capital”, by Mark Mitchell and Todd Pulvino is widely cited and goes into the gory detail. There were other factors that exacerbated the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on the convertible debt market such as market segmentation whereby investors in other asset classes were slow to move into the convertible debt market to correct mis-pricing following the forced withdrawal of the hedge funds (more detail on this impact in this paper from 2013).

Prior to the crisis, convertible arb hedge funds dominated the convertible bond market responsible for up-to 80% of activity. Today, the market is dominated by long only investors with hedge funds only reported to be responsible for 25% of activity with those hedge funds operating at much lower leverage levels (prime brokers are restricted to leverage of less than 1.5 times these days with recent talk of an outright rehypothecation ban for certain intermediaries on the cards). One of the funds that made it through the crash, Ferox Capital, stated in an article that convertible bonds have “become the play thing of long only investors” and that the “lack of technically-driven capital (hedge funds and proprietary trading desks) should leave plenty of alpha to be collected in a relatively low-risk manner” (well they would say that wouldn’t they!).

The reason for my interest in this topic is that one of the firms I follow just announced a convertible issue and I wanted to find out if my initial negative reaction is still justified. [I will be posting an update on my thoughts concerning the firm in question, Trinity Biotech, after their Q1 results due this week].

Indeed, the potential rehabilitation of convertible bonds to today’s investors is highlighted by the marketing push from people like EY and Credit Suisse on the benefits of convertible bonds as an asset class to insurers (as per their recent reports here and here). EY highlight the benefit of equity participation with downside protection, the ability to de-risk portfolios, and the use of convertible bonds to hedge equity risk. Credit Suisse, bless their little hearts, go into more technical detail about how convertibles can be used to lower the solvency requirement under Solvency II and/or for the Swiss Solvency Test.

With outstanding issuances estimated at $500 billion, the market has survived its turbulent past and it looks like there is life left in the old convertible bond magic dog yet.