In an opinion piece in the FT in 2008, Alan Greenspan stated that any risk model is “an abstraction from the full detail of the real world”. He talked about never being able to anticipate discontinuities in financial markets, unknown unknowns if you like. It is therefore depressing to see articles talk about the “VaR shock” that resulted in the Swissie from the decision of the Swiss National Bank (SNB) to lift the cap on its FX rate on the 15th of January (examples here from the Economist and here in the FTAlphaVille). If traders and banks are parameterising their models from periods of unrepresentative low volatility or from periods when artificial central bank caps are in place, then I worry that they are not even adequately considering known unknowns, let alone unknown unknowns. Have we learned nothing?

Of course, anybody with a brain knows (that excludes traders and bankers then!) of the weaknesses in the value-at-risk measure so beloved in modern risk management (see Nassim Taleb and Barry Schachter quotes from the mid 1990s on Quotes page). I tend to agree with David Einhorn when, in 2008, he compared the metric as being like “an airbag that works all the time, except when you have a car accident“. A piece in the New York Times by Joe Nocera from 2009 is worth a read to remind oneself of the sad topic.

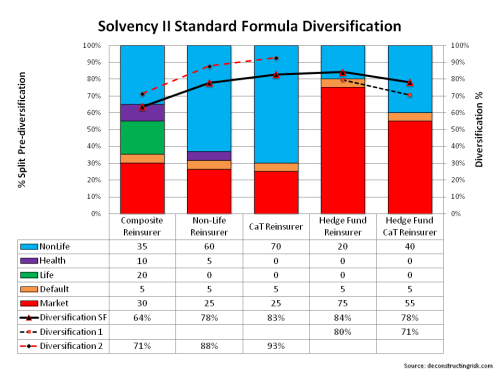

This brings me to the insurance sector. European insurance regulation is moving rapidly towards risk based capital with VaR and T-VaR at its heart. Solvency II calibrates capital at 99.5% VaR whilst the Swiss Solvency Test is at 99% T-VaR (which is approximately equal to 99.5%VaR). The specialty insurance and reinsurance sector is currently going through a frenzy of deals due to pricing and over-capitalisation pressures. The recently announced Partner/AXIS deal follows hot on the heels of XL/Catlin and RenRe/Platinum merger announcements. Indeed, it’s beginning to look like the closing hours of a swinger’s party with a grab for the bowl of keys! Despite the trend being unattractive to investors, it highlights the need to take out capacity and overhead expenses for the sector.

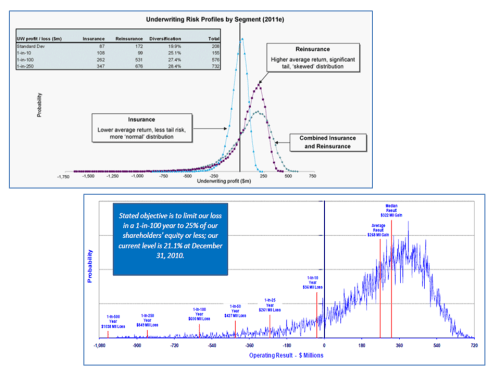

I have posted previously on the impact of reduced pricing on risk profiles, shifting and fattening distributions. The graphic below is the result of an exercise in trying to reflect where I think the market is going for some businesses in the market today. Taking previously published distributions (as per this post), I estimated a “base” profile (I prefer them with profits and losses left to right) of a phantom specialty re/insurer. To illustrate the impact of the current market conditions, I then fattened the tail to account for the dilution of terms and conditions (effectively reducing risk adjusted premia further without having a visible impact on profits in a low loss environment). I also added risks outside of the 99.5%VaR/99%T-VaR regulatory levels whilst increasing the profit profile to reflect an increase in risk appetite to reflect pressures to maintain target profits. This resulted in a decrease in expected profit of approx. 20% and an increase in the 99.5%VaR and 99.5%T-VaR of 45% and 50% respectively. The impact on ROEs (being expected profit divided by capital at 99.5%VaR or T-VaR) shows that a headline 15% can quickly deteriorate to a 7-8% due to loosening of T&Cs and the addition of some tail risk.

For what it is worth, T-VaR (despite its shortfalls) is my preferred metric over VaR given its relative superior measurement of tail risk and the 99.5%T-VaR is where I would prefer to analyse firms to take account of accumulating downside risks.

The above exercise reflects where I suspect the market is headed through 2015 and into 2016 (more risky profiles, lower operating ROEs). As Solvency II will come in from 2016, introducing the deeply flawed VaR metric at this stage in the market may prove to be inappropriate timing, especially if too much reliance is placed upon VaR models by investors and regulators. The “full detail of the real world” today and in the future is where the focus of such stakeholders should be, with much less emphasis on what the models, calibrated on what came before, say.