With the ending of the World Cup, my attention turned again to my attempts at understanding the issues facing the betting and gambling sector. For the sake of full disclosure, I am a novice on the sector (I am not a gambler if investing and the odd poker game are not included as such) and have no positions in any betting or gaming stock. My ramblings here, and in previous posts, simply illustrate my attempts to satisfy my curiosity about a sector that is at a fascinating point of change.

In a previous post, I highlighted the changes that the internet has had on the betting and gaming sectors. At that time, I thought the impact of the disintermediating betting exchanges on traditional business models could provide interesting insights into other disintermediating businesses in the financial sector. However, as I have found out more about the sector, such as the results of the traditional betting firms in the UK as per this post, there are a multitude of issues facing the sector such that a review of the impact of the betting exchanges in isolation is not that informative and (frankly) outdated given current developments. Recent developments include regulatory changes such as those in the US which has prompted the purchase of the largest online poker firm Pokerstars by approximately $5 billion by Amaya Gaming and new online taxes such as the forthcoming UK point of consumption (POC) tax of 15% due in December.

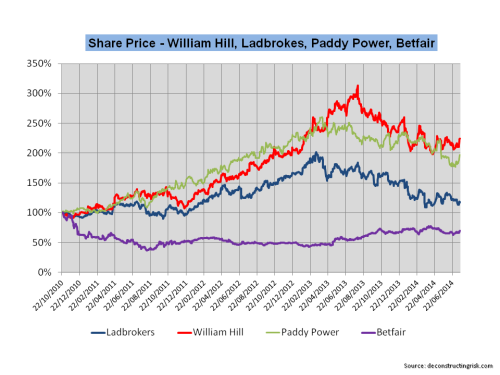

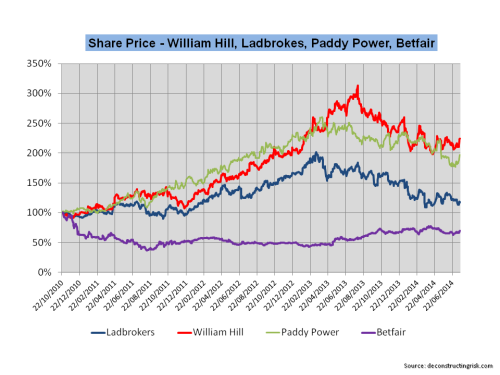

As the graph of Betfair’s share price since its floatation in late 2010 shows, the betting exchange model clearly has not had much of a disruptive impact on the traditional business models in recent years.

click to enlarge

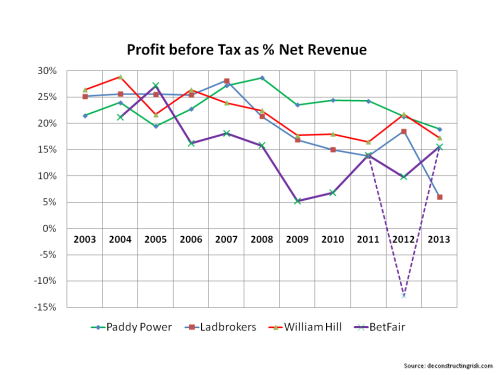

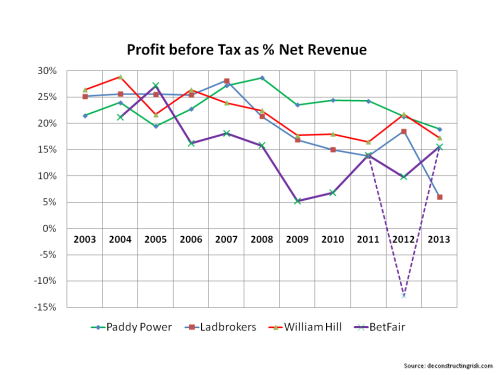

Rather than go over Betfair’s eventful past in detail here, I will focus on current issues. Niall O’Connor in his blog, bettingmarket.com, has a number of informative articles on the history of Betfair, including this one. Below, I show a graph of Betfair’s profit before tax against the other UK betting firms which illustrates its difficulties in the recent past. The 2012 results (which are Betfair’s YE 2013 results as their year ends in April) exclude some write-offs and adjustments as a result of Betfair’s turnaround plan (which are included in the dotted line). The plan involved refocusing on sustainable geographical betting markets with accommodative regulations and developing a fixed odds betting business alongside the exchange to optimise the liquidity advantages of each model.

The new plan, in effect, admitted that the stand alone betting exchange model was flawed and that some markets “may not have sufficient liquidity to offer an optimal betting experience, notably in ante post and ancillary markets“. The firm estimates its share of the sophisticated bettor market of £150 million at 60-70% but its share of the recreational and occasional bettor market of £500 million at less than 10%. This market is where they see growth and Breon Corcoran, previously Paddy Power’s COO, was brought in as Betfair’s new CEO in August 2012 to execute on the new direction. The most recent results show that the new strategy is delivering better results.

click to enlarge

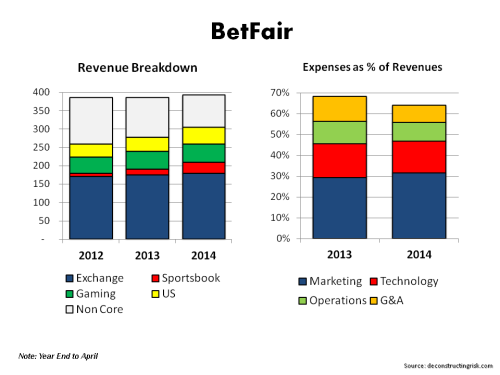

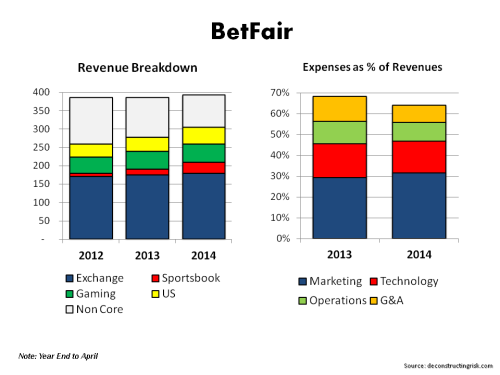

The focus on sustainable betting markets and cost cutting whilst increasing marketing spending (Betfair were high profile in recent World Cup advertising) can be seen in the graph below. Product development in features such as cash out and price rush (automatically gives the best odds from fixed odds and exchange) are being heavily pushed, particularly in the growingly important mobile market.

click to enlarge

As mentioned in the previous post, there is a vast body of academic research on the gambling market and with the wealth of data that Betfair offers, the betting exchange market has been no exception in the studies. The Institute for Strategy and Business Economics in the University of Zurich in particular has some interesting papers. This one, for example, contends that there is a growing body of evidence that exchange markets “exhibit high prediction accuracy as they regularly outperform non-market forecasting methods”. The well-documented long-shot bias where the tendency to overvalue underdogs by fixed odd markets “is less pronounced in person-to-person betting” and this can be used by traders on the betting exchange to arbitrage price differences.

There is a particularly interesting paper by Egon Franck, Raphael Flepp and Stephan Nüesch in the University of Zurich from December 2013 on the importance of liquidity in determining price competitiveness which the authors offer as one of the reasons behind BetFair’s move into fixed odds online betting. Other arbitrage opportunities indentified by research include bookmakers actively shading prices in the presence of a partly irrational betting audience in order to increase their profit (e.g. sentiment bias in football games by the home fans) or the movement in odds prior and during games with the growth of in-play betting.

The development of sports investment funds was previously highlighted in a Bloomberg article and despite an early hic-cup with the collapse of a fund called Centaur there are many now developing predictive algorithms which try to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities. BetFair is consistently looking at how it can optimise its pricing (on the exchange it earns its commissions on winnings by a sliding scale on volume) in different geographical areas and sports to maximise its commissions, despite an outcry from a pricing charge change a few years ago.

Although BetFair face considerable challenges (e.g. I estimate that 95% of BetFair’s sustainable revenues are concentrated in the UK and the firm disclosed that the POC tax, if implemented as currently envisaged, would of cost them £36 million for their 2014 year, one with £61 million of operating profit!) in the short to medium term, one of their strengths is the balance sheet with a net asset ratio of 55% and a cash pile of over £200 million and a strong cash generating business. In their latest results Corcoran commented that “the flexibility we retain through our strong balance sheet provides a competitive advantage during uncertain times for the gaming sector. We will continue to review our balance sheet on a regular basis.” Although Betfair are a fascinating case to keep an eye on, the uncertainties on the POC tax issues outweigh any positive investment case for now.

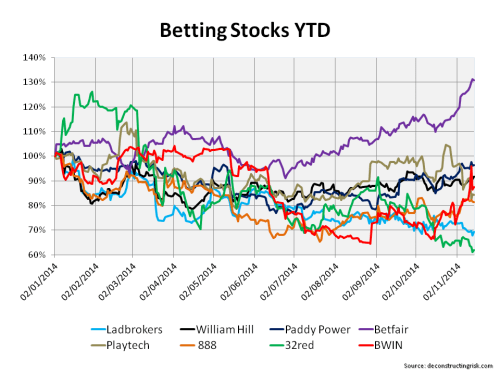

In my attempts at understanding the sector more, these comments led me to look at some other models (and possible acquisition targets) in the other publically traded online firms, mainly on the gaming side. Names that I have looked at include 888, BWIN (currently looking at strategic options!) and 32Red. I am also intrigued by the software gaming firm Playtech which provides the underlying software to many firms in the sector. I will follow-up with a post on further musings.