Walk around any office today and you will likely see staff on the internet or playing with their smartphones, the extent of which will depend upon the office etiquette. The rise of the networked society would intuitively imply increased productivity. Data analytics, the cloud, the ease with which items can be researched and purchased all imply a rise in efficiency and productivity. Or does it?

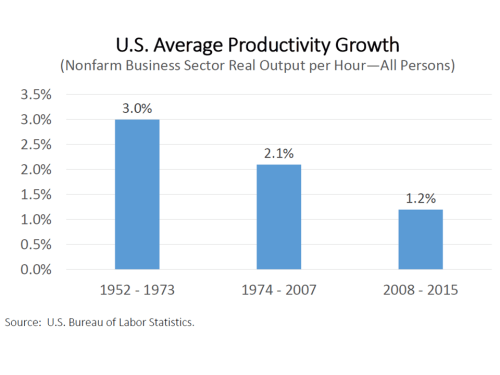

Productivity is about “working smarter” rather than “working harder” and it reflects our ability to produce more output by better combining inputs, owing to new ideas, technological innovations and business models. Productivity is critical to future growth. Has the rise of social media, knowing what your friends favourite type of guacamole is, made any difference to productivity? The statistics from recent years indicate the answer is no with the slowdown in productivity vexing economists with a multitude of recent opinion and papers on the topic. Stanley Fisher from the Fed stating in an interesting speech for earlier this month that “we simply do not know what will happen to productivity growth” and included the graph below in his presentation.

Martin Wolf in a piece in the FT on recent projections by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) calls the prospects for productivity “the most important uncertainty affecting economic prospects of the British people”.

Some think the productivity statistics have misestimated growth and the impact of technology (e.g. the amount of free online services). A recent paper from earlier this month by Fed and IMF employees Byrne, Fernald and Reinsdorf concluded that “we find little evidence that the slowdown arises from growing mismeasurement of the gains from innovation in IT-related goods and services”.

The good news seems to be that productivity slumps are far from unprecedented according to a paper in September last year from Eichengreen, Park and Shin. The bad news is that the authors conclude the current slump is widespread and evident in advanced countries like the U.S. and UK as well as in emerging markets in Latin America, Southeast Europe and Central Asia including China.

A fascinating paper from December 2015 by staff at the Bank of England called “Secular drivers of the global real interest rate” covers a wide range of issues which are impacting growth, including productivity growth. I am still trying to digest much of the paper but it does highlight many of the economists’ arguments on productivity.

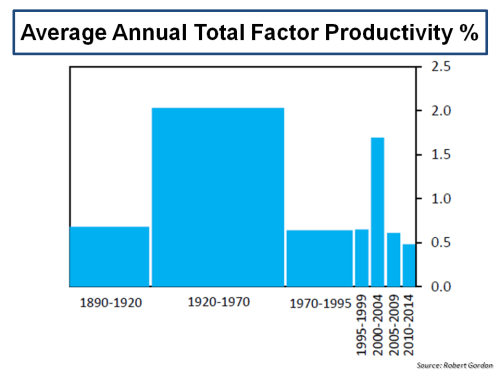

One of those is Robert Gordon, who has a new bestseller out called “The Rise and Fall of American Growth”. Gordon has long championed the view of a stagnation in technology advances due to structural headwinds such as an educational plateau, income inequality and public indebtedness.

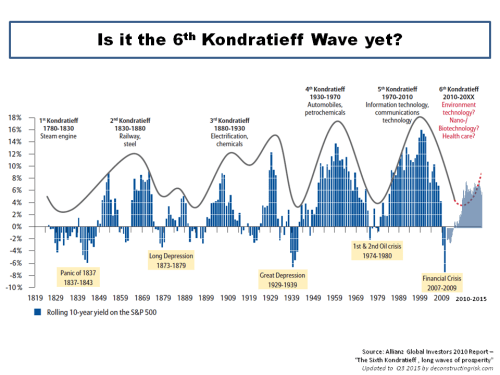

Others argue that productivity comes in waves and new technology often takes time to be fully integrated into the production process (e.g. electricity took 20 years before the benefits showed in labour productivity).

Clearly this is an important issue and one which deserves the current level of debate. Time will tell whether we are in a slump and will remain there or whether we are at the dawn of a golden era of innovation led productivity growth…..