Scenario and stress testing by financial regulators has become a common supervisory tool since the financial crisis. The EU, the US and the UK all now regularly stress their banks using detailed adverse scenarios. In a recent presentation, Moody’s Analytics illustrated the variation in some of the metrics in the adverse scenarios used in recent tests by regulators, as per the graphic below of the peak to trough fall in real GDP.

Many commentators have criticized these tests for their inconsistency and flawed methodology while pointing out the political conflict many regulators with responsibility for financial stability have. They cannot be seen to be promoting a draconian scenario for stress testing on the one hand whilst assuring markets of the stability of the system on the other hand.

The EU tests have particularly had a credibility problem given the political difficulties in really stressing possible scenarios (hello, a Euro break-up?). An article last year by Morris Goldstein stated:

“By refusing to include a rigorous leverage ratio test, by allowing banks to artificially inflate bank capital, by engaging in wholesale monkey business with tax deferred assets, and also by ruling out a deflation scenario, the ECB produced estimates of the aggregate capital shortfall and a country pattern of bank failures that are not believable.”

In a report from the Adam Smith Institute in July, Kevin Dowd (a vocal critic of the regulator’s approach) stated that the Bank of England’s 2014 tests were lacking in credibility and “that the Bank’s risk models are worse than useless because they give false risk comfort”. Dowd points to the US where the annual Comprehensive Capital Assessment and Review (CCAR) tests have been supplemented by the DFAST tests mandated under Dodd Frank (these use a more standard approach to provide relative tests between banks). In the US, the whole process has been turned into a vast and expensive industry with consultants (many of them ex-regulators!) making a fortune on ever increasing compliance requirements. The end result may be that the original objectives have been somewhat lost.

According to a report from a duo of Columba University professors, banks have learned to game the system whereby “outcomes have become more predictable and therefore arguably less informative”. The worry here is that, to ensure a consistent application across the sector, regulators have been captured by their models and are perpetuating group think by dictating “good” and “bad” business models. Whatever about the dangers of the free market dictating optimal business models (and Lord knows there’s plenty of evidence on that subject!!), relying on regulators to do so is, well, scary.

To my way of thinking, the underlying issue here results from the systemic “too big to fail” nature of many regulated firms. Capitalism is (supposedly!) based upon punishing imprudent risk taking through the threat of bankruptcy and therefore we should be encouraging a diverse range of business models with sensible sizes that don’t, individually or in clusters, threaten financial stability.

On the merits of using stress testing for banks, Dowd quipped that “it is surely better to have no radar at all than a blind one that no-one can rely upon” and concluded that the Bank of England should, rather harshly in my view, scrap the whole process. Although I agree with many of the criticisms, I think the process does have merit. To be fair, many regulators understand the limitations of the approach. Recently Deputy Governor Jon Cunliffe of the Bank of England admitted the fragilities of some of their testing and stated that “a development of this approach would be to use stress testing more counter-cyclically”.

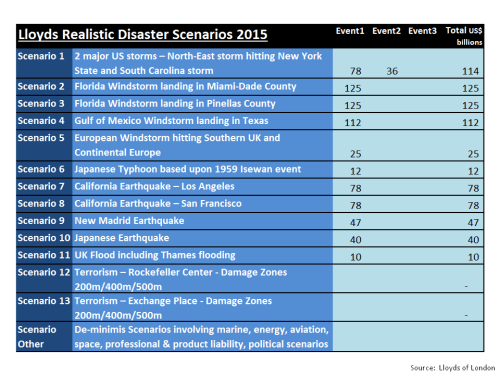

The insurance sector, particularly the non-life sector, has a longer history with stress and scenario testing. Lloyds of London has long required its syndicates to run mandatory realistic disaster scenarios (RDS), primarily focussed on known natural and man-made events. The most recent RDS are set out in the exhibit below.

A valid criticism of the RDS approach is that insurers know what to expect and are therefore able to game the system. Risk models such as the commercial catastrophe models sold by firms like RMS and AIR have proven ever adapt at running historical or theoretical scenarios through today’s modern exposures to get estimates of losses to insurers. The difficulty comes in assigning probabilities to known natural events where the historical data is only really reliable for the past 100 years or so and where man-made events in the modern world, such as terrorism or cyber risks, are virtually impossible to predict. I previously highlighted some of the concerns on the methodology used in many models (e.g. on correlation here and VaR here) used to assess insurance capital which have now been embedded into the new European regulatory framework Solvency II, calibrated at a 1-in-200 year level.

The Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA), now part of the Bank of England, detailed a set of scenarios last month to stress test its non-life insurance sector in 2015. The detail of these tests is summarised in the exhibit below.

Robert Childs, the chairman of the Hiscox group, raised some eye brows by saying the PRA tests did not go far enough and called for a war game type exercise to see “how a serious catastrophe may play out”. Childs proposed that such an exercise would mean that regulators would have the confidence in industry to get on with dealing with the aftermath of any such catastrophe without undue fussing from the authorities.

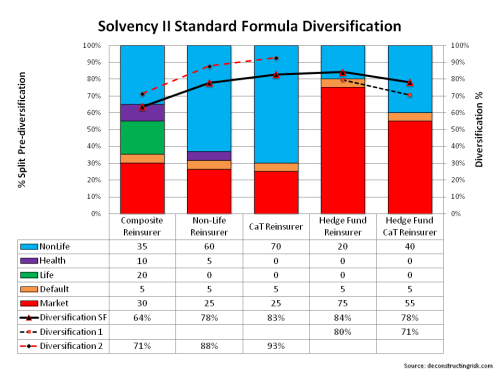

An efficient insurance sector is important to economic growth and development by facilitating trade and commerce through risk mitigation and dispersion, thereby allowing firms to more effectively allocate capital to productive means. Too much “fussing” by regulators through overly conservative capital requirements, maybe resulting from overtly pessimistic stress tests, can result in economic growth being impinged by excess cost. However, given the movement globally towards larger insurers, which in my view will accelerate under Solvency II given its unrestricted credit for diversification, the regulator’s focus on financial stability and the experiences in banking mean that fussy regulation will be in vogue for some time to come.

The scenarios selected by the PRA are interesting in that the focus for known natural catastrophes is on a frequency of large events as opposed to an emphasis on severity in the Lloyds’ RDS. It’s arguable that the probability of the 2 major European storms in one year or 3 US storms in one year is significantly more remote than the 1 in 200 probability level at which capital is set under Solvency II. One of the more interesting scenarios is the reverse stress test such that the firm becomes unviable. I am sure many firms will select a combination of events with an implied probability of all occurring with one year so remote as to be impossible. Or select some ultra extreme events such as the Cumbre Vieja mega-tsunami (as per this post). A lack of imagination in looking at different scenarios would be a pity as good risk management should be open to really testing portfolios rather than running through the same old known events.

New scenarios are constantly being suggested by researchers. Swiss Re recently published a paper on a reoccurrence of the New Madrid cluster of earthquakes of 1811/1812 which they estimated could result in $300 billion of losses of which 50% would be insured (breakdown as per the exhibit below). Swiss Re estimates the probability of such an event at 1 in 500 years or roughly a 10% chance of occurrence within the next 50 years.

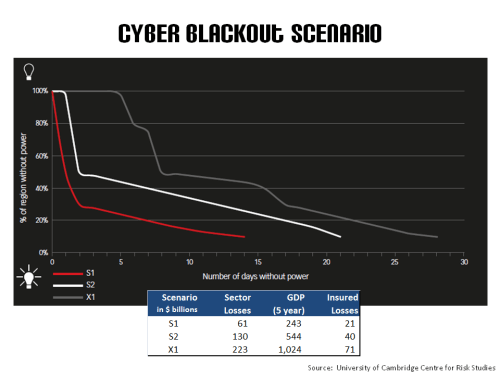

Another interesting scenario, developed by the University of Cambridge and Lloyds, which is technologically possible, is a cyber attack on the US power grid (in this report). There have been a growing number of cases of hacking into power grids in the US and Europe which make this scenario ever more real. The authors estimate the event at a 1 in 200 year probability and detail three scenarios (S1, S2, and the extreme X1) with insured losses ranging from $20 billion to $70 billion, as per the exhibit below. These figures are far greater than the probable maximum loss (PML) estimated for the sector by a March UK industry report (as per this post).

I think it will be a very long time before any insurer willingly publishes the results of scenarios that could cause it to be in financial difficulty. I may be naive but I think that is a pity because insurance is a risk business and increased transparency could only lead to more efficient capital allocations across the sector. Everybody claiming that they can survive any foreseeable event up to a notional probability of occurrence (such as 1 in 200 years) can only lead to misplaced solace. History shows us that, in the real world, risk has a habit of surprising, and not in a good way. Imaginative stress and scenario testing, performed in an efficient and transparent way, may help to lessen the surprise. Nothing however can change the fact that the “unknown unknowns” will always remain.