The market has a tendency to take an extreme position, either everything is on the up or the sky is about to fall in. Well, fear is the flavour of the markets these days and that’s no bad thing given where we have come from. Still it’s annoying to hear the media full of hysterical noise on Ebola, the Middle East, Europe, Japan, Russia, oil, end of QE, deflation, etc. Hopefully, we’ll start to get some more considered arguments on what the medium term economic and earnings outlook may look like. Vitaliy Katsenelson had a nice piece on thinking through the effects of a few scenarios. Hopefully, the end of the happy-clappy market (it will likely not go easily and may well return before long) will lead to some more thoughtful pieces like that.

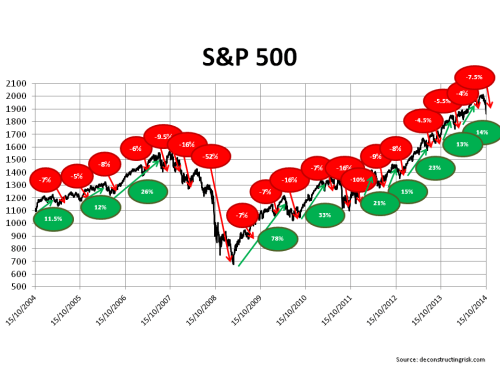

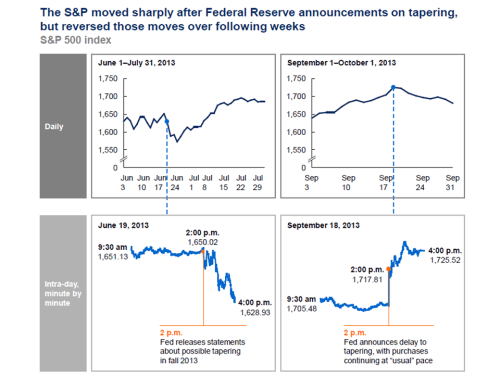

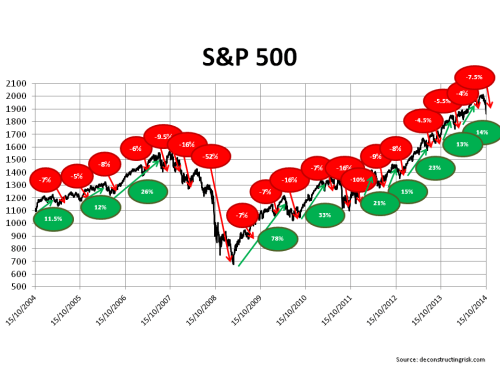

For now though, the smell of fear is in the air and the graph below on the ups and downs in the S&P500 show that the recent volatility is not even near correction territory (i.e. greater than 10% fall). In fact, we really haven’t had a proper correction since late 2011. As to whether this volatility will turn into a correction, I have no idea (I suspect it might take a while yet but it will get there).

click to enlarge

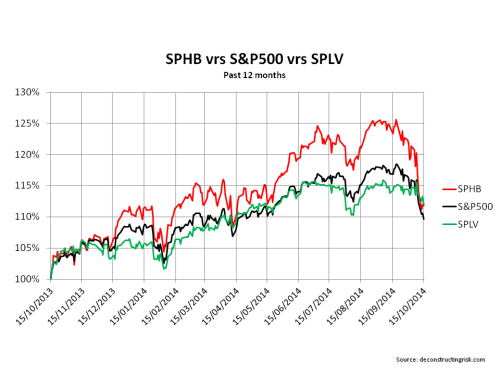

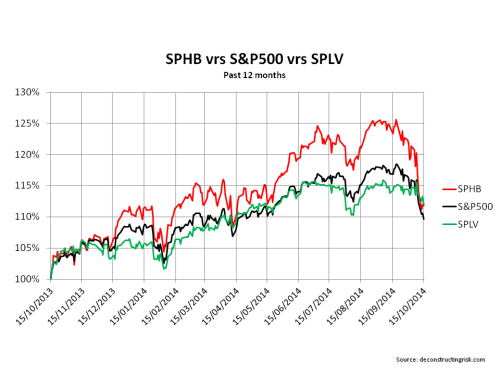

The graph below shows that the high beta stocks as measured by the Powershares high beta ETF (SPHB), as you would expect, have been hit hard here compared to the S&P500 and the low volatility ETF.

click to enlarge

It will be interesting to see how the market develops over the coming weeks. Earnings, particularly guidance for Q4, will likely play a large part it how it plays out.

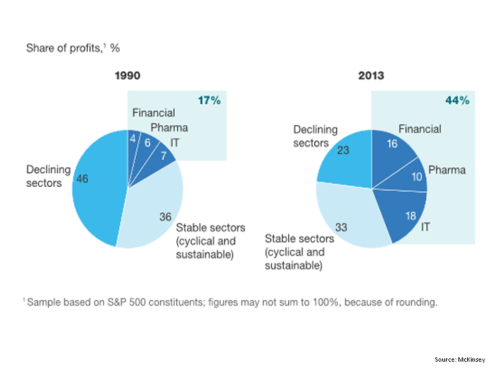

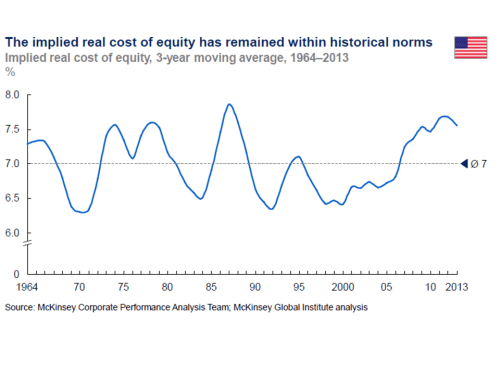

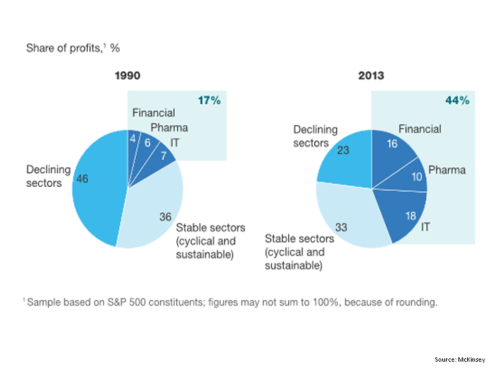

On the debate about whether historically high earnings can continue, McKinsey had an interesting article recently on the earnings and the market. The graph below from McKinsey illustrates the increased important of technology, pharma, and financials in the higher profits.

click to enlarge

Spending time looking for thoughtful arguments on the impact of macro-economic, demographic and social pressure in today’s world on these sectors is a better way to understanding the medium term direction of the market. As McKinsey says “assessing the market’s current value ultimately depends on whether the profit margins are sustainable”. The rest is really just noise, best ignored or viewed from a distance.