As the horde of middle aged (still mainly male) executives pack up their chinos and casual shirts, the overriding theme coming from this year’s Monte Carlo Renez-Vous seems to be impact of the new ILS capacity or “convergence capital” on the reinsurance and specialty insurance sector. The event, described in a Financial Times article as “the kind of public display of wealth most bankers try to eschew”, is where executives start the January 1 renewal discussions with clients in quick meetings crammed together in the luxury location.

The relentless chatter about the new capital will likely leave many bored senseless of the subject. Many may now hope that, just like previous hot discussion topics that were worn out (Solvency II anybody?), the topic fades into the background as the reality of the office huts them next week.

The more traditional industry hands warned of the perils of the new capacity on underwriting discipline. John Nelson of Lloyds highlighted that “some of the structures being used could undermine some of the qualities of the insurance model”. Tad Montross of GenRe cautioned that “bankers looking to replace lost fee income” are pushing ILS as the latest asset class but that the hype will die down when “the inability to model extreme weather events accurately is better understood”. Amer Ahmed of Allianz Re predicted the influx “bears the danger that certain risks get covered at inadequate rates”. Torsten Jeworrek of Munich Re said that “our research shows that ILS use the cheapest model in the market” (assumingly in a side swipe at AIR).

Other traditional reinsurers with an existing foothold in the ILS camp were more circumspect. Michel Lies of Swiss Re commented that “we take the inflow of alternative capital seriously but we are not alarmed by it”.

Brokers and other interested service providers were the loudest cheerleaders. Increasing the size of the pie for everybody, igniting coverage innovative in the traditional sector, and cheap retrocession capacity were some of the advantages cited. My favourite piece of new risk management speak came from Aon Benfield’s Bryon Ehrhart in the statement “reinsurers will innovate their capital structures to turn headwinds from alternative capital sources into tailwinds”. In other words, as Tokio Millennium Re’s CEO Tatsuhiko Hoshina said, the new capital offers an opportunity to leverage increasingly diverse sources of retrocessional capacity. An arbitrage market (as a previous post concluded)?

All of this talk reminds me of the last time that “convergence” was a buzz word in the sector in the 1990s. For my sins, I was an active participant in the market then. Would the paragraph below from an article on insurance and capital market convergence by Graciela Chichilnisky of Columbia University in June 1996 sound out of place today?

“The future of the industry lies with those firms which implement such innovation. The companies that adapt successfully will be the ones that survive. In 10 years, these organizations will draw the map of a completely restructured reinsurance industry”

The current market dynamics are driven by low risk premia in capital markets bringing investors into competition with the insurance sector through ILS and collaterised structures. In the 1990s, capital inflows after Hurricane Andrew into reinsurers, such as the “class of 1992”, led to overcapacity in the market which resulted in a brutal and undisciplined soft market in the late 1990s.

Some (re)insurers sought to diversify their business base by embracing innovation in transaction structures and/or by looking at expanding the risks they covered beyond traditional P&C exposures. Some entered head first into “finite” type multi-line multi-year programmes that assumed structuring could protect against poor underwriting. An over-reliance on the developing insurance models used to price such transactions, particularly in relation to assumed correlations between exposures, left some blind to basic underwriting disciplines (Sound familiar, CDOs?). Others tested (unsuccessfully) the limits of risk transfer and legality by providing limited or no risk coverage to distressed insurers (e.g. FAI & HIH in Australia) or by providing reserve protection that distorted regulatory requirements (e.g. AIG & Cologne Re) by way of back to back contracts and murky disclosures.

Others, such as the company I worked for, looked to cover financial risks on the basis that mixing insurance and financial risks would allow regulatory capital arbitrage benefits through increased diversification (and may even offer an inflation & asset price hedge). Some well known examples* of the financial risks assumed by different (re)insurers at that time include the Hollywood Funding pool guarantee, the BAe aircraft leasing income coverage, Rolls Royce residual asset guarantees, dual trigger contingent equity puts, Toyota motor residual value protection, and mezzanine corporate debt credit enhancement coverage.

Many of these “innovations” ended badly for the industry. Innovation in itself should never be dismissed as it is a feature of the world we live in. In this sector however, innovation at the expense of good underwriting is a nasty combination that the experience in the 1990s must surely teach us.

Bringing this back to today, I recently discussed the ILS market with a well informed and active market participant. He confirmed that some of the ILS funds have experienced reinsurance professionals with the skills to question the information in the broker pack and who do their own modelling and underwriting of the underlying risks. He also confirmed however that there is many funds (some with well known sponsors and hungry mandates) that, in the words of Kevin O’Donnell of RenRe, rely “on a single point” from a single model provided by to them by an “expert” 3rd party.

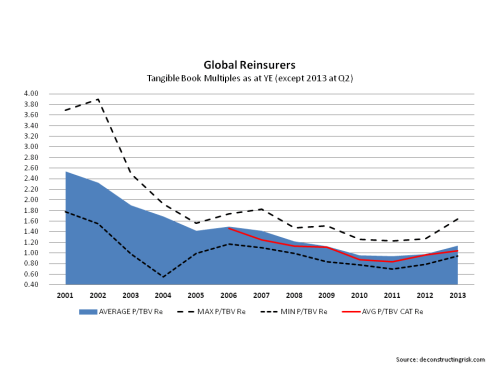

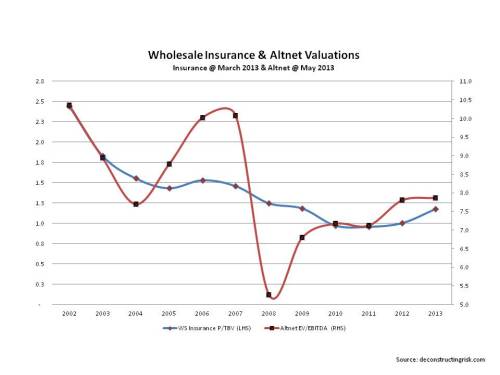

This conversation got me to thinking again about the comment from Edward Noonan of Validus that “the ILS guys aren’t undisciplined; it’s just that they’ve got a lower cost of capital.” Why should an ILS fund have a lower cost of capital to a pure property catastrophe reinsurer? There is the operational risk of a reinsurer to consider. However there is also operational risk involved with an ILS fund given items such as multiple collateral arrangements and other contracted 3rd party service provided functions to consider. Expenses shouldn’t be a major differing factor between the two models. The only item that may justify a difference is liquidity, particularly as capital market investors are so focussed on a fast exit. However, should this be material given the exit option of simply selling the equity in many of the quoted property catastrophe reinsurers?

I am not convinced that the ILS funds should have a material cost of capital advantage. Maybe the quoted reinsurers should simply revise their shareholder return strategies to be more competitive with the yields offered by the ILS funds. Indeed, traditional reinsurers in this space may argue that they are able to offer more attractive yields to a fully collaterised provider, all other things being equal, given their more leveraged business model.

*As a complete aside, an article this week in the Financial Times on the anniversary of the Lehman Brothers collapse and the financial crisis highlighted the role of poor lending practices as a primary cause of significant number of the bank failures. This article reminded me of a “convergence” product I helped design back in the late 1990s. Following changes in accounting rules, many banks were not allowed to continue to hold general loan loss provisions against their portfolio. These provisions (akin to an IBNR type bulk reserve) had been held in addition to specific loan provision (akin to case reserves). I designed an insurance structure for banks to pay premiums previously set aside as general provisions for coverage on massive deterioration in their loan provisions. After an initial risk period in which the insurer could lose money (which was required to demonstrate an effective risk transfer), the policy would act as a fully funded coverage similar to a collaterised reinsurance. In effect the banks could pay some of the profits in good years (assuming the initial risk period was set over the good years!) for protection in the bad years. The attachment of the coverage was designed in a way similar to the old continuous ratcheting retention reinsurance aggregate coverage popular at the time amongst some German reinsurers. After numerous discussions, no banks were interested in a cover that offered them an opportunity to use profits in the good times to buy protection for a rainy day. They didn’t think they needed it. Funny that.