There is little doubt that the financial services industry is currently facing many challenges and undergoing a generational change. The US economist Thomas Philippon opined that the finance industry over-expansion in the US means that it’s share of GDP is about 2 percentage points higher than it needs to be although he has also estimated that the unit cost of intermediation hasn’t changed significantly in recent years, despite advances in technology and the regulatory assaults upon the industry following the financial crisis.

The insurance sector has its own share of issues. Ongoing low interest rates and inflation, broader low risk premia across the capital markets, rapid technology changes such as big data and the onset of real time underwriting are just the obvious items. The Economist had an article in March that highlighted the prospective impact of data monitoring and technology on the underwriting of motor and health risks. This is another interesting post on a number of the new peer to peer business models such as Friendsurance, Bought by Many, and Guevara who are trying to disrupt the insurance sector. There can be little doubt that the insurance industry, just like other financial sectors, will be impacted by such secular trends.

However, this post is primarily focused on the short to medium term outlook for the specialty insurance and reinsurance sector. I have been asked a few of times by readers to outline what I think the next few years may look like for this sector. My views of the current market were nicely articulated by Alex Maloney, the Group CEO of Lancashire, who commented in their recent quarterly results statement as follows:

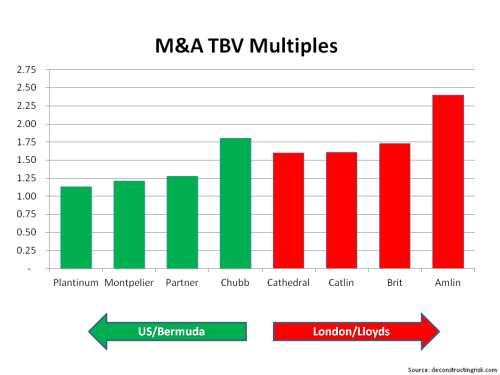

“The year to date has seen a flurry of activity on the M&A front within the industry, much of this, in my view, is driven by the need to rationalise and refocus oversized and over stretched businesses. We also continue to see a bout of initiatives and innovations in the market, the sustainability and longer term viability of which are questionable. These are symptoms of where we are in the cycle. We have seen these types of trends before and in all likelihood, will see them again.”

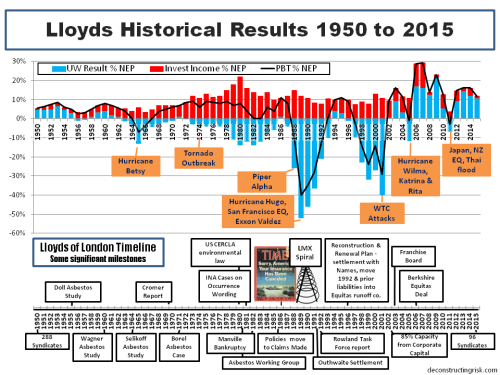

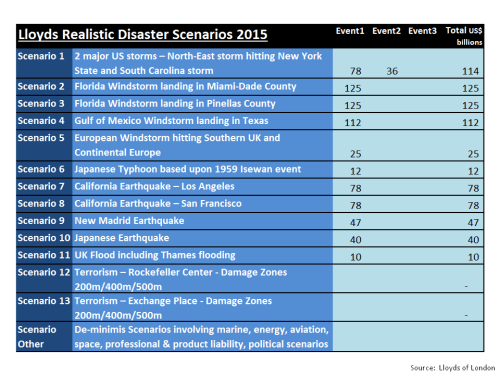

Lloyds of London has had a colourful past and many of its historical issues are specific to it and reflective of its own eccentric ways. However, as a proxy for the global specialty sector, particularly over the past 20 years, it provides some interesting context on the trends we find ourselves in today. Using data from Lloyds with some added flavour from my experiences, the graphic below shows the dramatic history of the market since 1950.

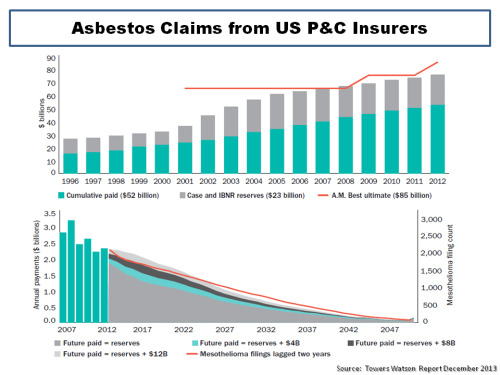

The impact of Hurricane Betsy in 1965 upon Lloyds illustrated a number of the fault-lines in the structure of Lloyds with the subsequent Cromer report warning on the future danger of unequal treatment between insiders (aka working Names) and “dumb” capital providers (aka all other Names). The rapid influx of such ill informed capital in the late 1970s and the 1980s laid the seeds of the market’s near destruction largely due to the tsunami of US liability claims resulting from asbestos and pollution exposures in the 1980s. These losses were exacerbated by the way Lloyds closed underwriting years to future capital providers through vastly underpriced reinsurance to close transactions and the practice of the incestuous placement of excess of loss retrocession for catastrophe losses within the market, otherwise known as the London Market Excess of Loss (LMX) spiral. There is a clever article by Joy Schwartzman from 2008 on the similarity between the LMX spiral and the financial risk transformational illusions that featured heavily in the financial crisis. Indeed, the losses from the sloppy “occurrence” liability insurance policy wordings and the tragedy of unheeded asbestos risks continued to escalate well into the 1990s, as the exhibit below from a 2013 Towers Watson update illustrates.

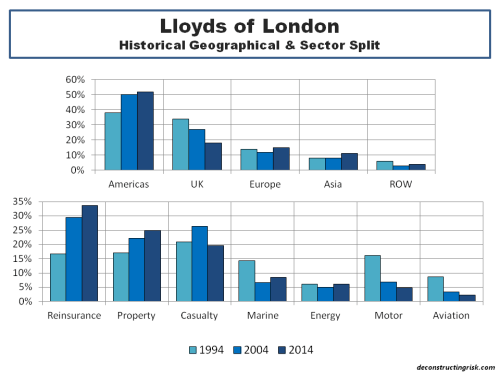

What happened in Lloyds after the market settlement with Names and the creation of the “bad bank” Equitas for the 1992 and prior losses is where the lessons of Lloyds are most applicable to the market today. The graphic below shows the geographical and business split of Lloyds over the past 20 years, showing that although the underlying risk and geographical mix has changed it remains a diversified global business.

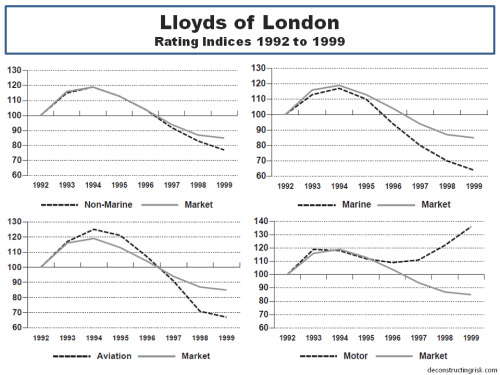

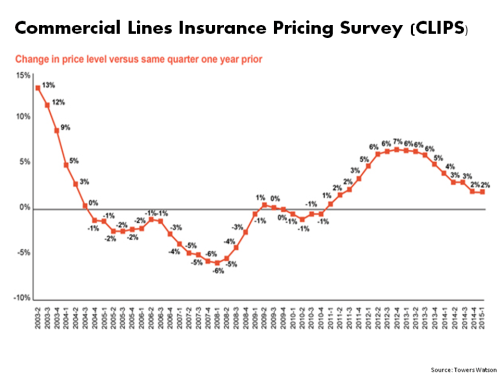

Released from the burden of the past after the creation of Equitas, the market quickly went on what can only be described as an orgy of indiscipline. The pricing competition was brutal in the last half of the 1990s with terms and conditions dramatically widened. Rating indices published by the market, as below, at the time show the extent of the rate decreases although the now abandoned underwriting indices published at the same time spectacularly failed to show the impact of the loosening of T&Cs.

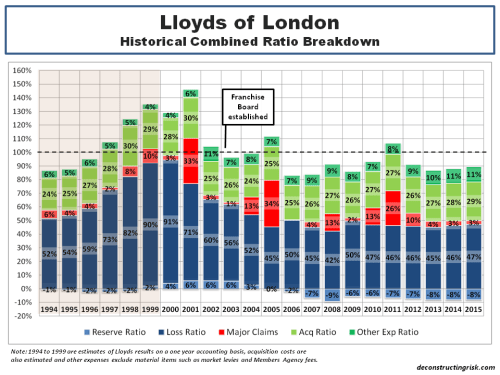

As Lloyds moved from their historical three year accounting basis in the 2000s it’s difficult to compare historical ratios from the 1990s. Notwithstanding this, I did made an attempt to reconcile combined ratios from the 1990s in the exhibit below which clearly illustrates the impact market conditions had on underwriting results.

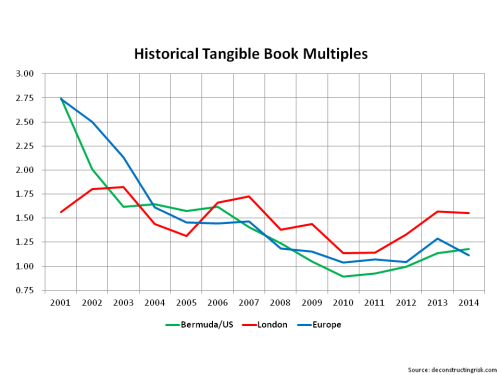

The Franchise Board established in 2003, under the leadership of the forthright and highly effective Rolf Tolle, was created to enforce market discipline in Lloyds after the disastrous 1990s. The combined ratios from recent years illustrate the impact it has had on results although the hard market after 9/11 provided much of the impetus. The real test of the Franchise Board will be outcome of the current soft market. The rating indices published by Amlin, as below, show where rates are currently compared to the rates in 2002 (which were pushed up to a level following 2001 to recover most of the 1990s fall-off). Rating indices published by Lancashire also confirm rate decreases of 20%+ since 2012 in lines like US property catastrophe, energy and aviation.

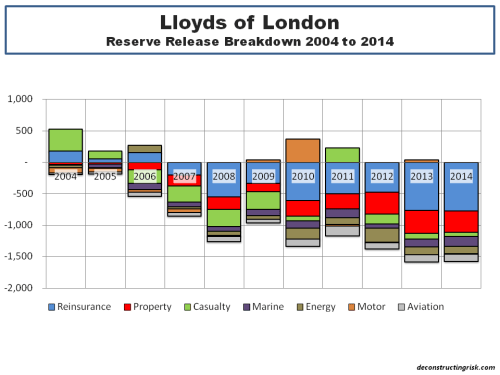

The macro-economic environment and benign claims inflation over the past several years has clearly helped loss ratios. A breakdown of the recent reserve releases, as below, show that reinsurance and property remain important sources of releases (the reinsurance releases are also heavily dependent on property lines).

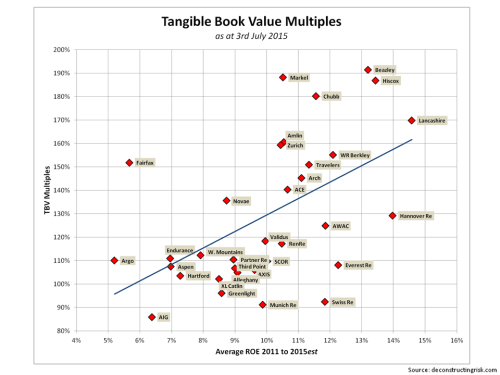

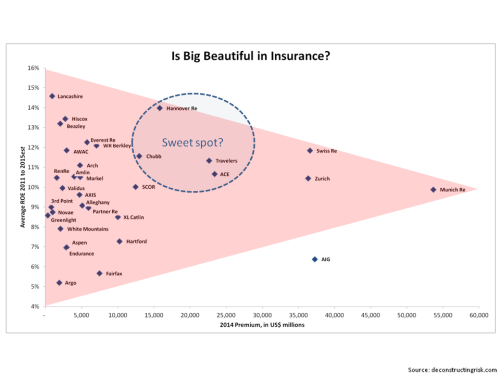

Better discipline and risk management have clearly played their part in the 10 year average ROE of 15% (covering 2005 to 2014 with the 2005 and 2011 catastrophe years included). The increasing overhead expenses are an issue for Lloyds, recently causing Ed Noonan of Validus to comment:

“We think that Lloyd’s remains an outstanding market for specialty business and their thrust towards international diversification is spot on from a strategic perspective. However, the costs associated with Lloyd’s and the excessive regulation in the UK are becoming significant issues, as is the amount of management and Board time spent on compliance well beyond what’s necessary to ensure a solvent and properly functioning market. Ultimately, this smothering regulatory blanket will drive business out of Lloyd’s and further the trend of placement in local markets.”

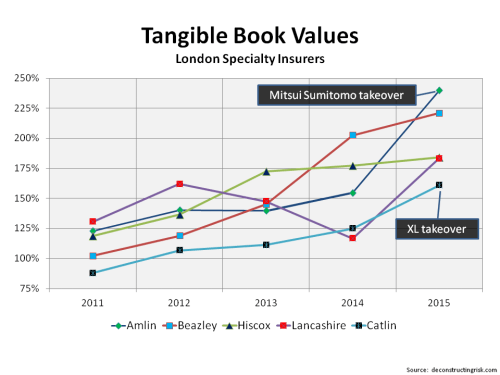

So what does all of this tell us about the next few years? Pricing and relaxed terms and conditions will inevitably have an impact, reserve releases will dry up particularly from reinsurance and property, investment returns may improve and claim inflation may increase but neither materially so, firms will focus on expense reduction whilst dealing with more intrusive regulation, and the recent run of low catastrophic losses will not last. ROEs of low double digits or high single digits does not, in my view, compensate for these risks. Longer term the market faces structural changes, in the interim it faces a struggle to deliver a sensible risk adjusted return.