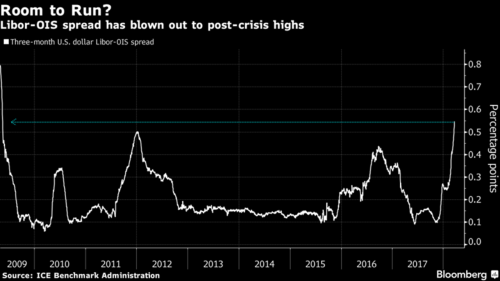

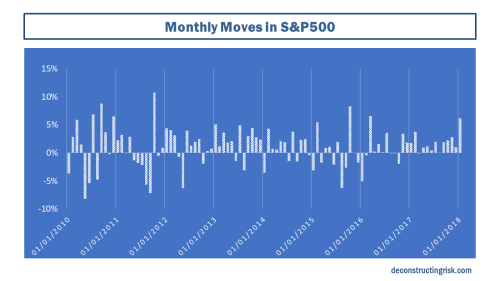

Whatever measure you look at, equities in the US are overvalued, arguably in bubble territory. Investors poured record amounts into equity funds in recent weeks as the market melt-up takes hold. One of the intriguing features of the bull market over the past 18 months has been the extraordinary low volatility. Hamish Preston of S&P Dow Jones Indices estimated that the average observed 1-month volatility in the S&P 500 in 2017 is “lower than in any other year since 1970”. To illustrate the point, the graph below shows the monthly change in the S&P500 over recent years.

click to enlarge

The lack of any action below 0% since November 2016 and any pullback greater than 2% since January 2016 is striking. “Don’t confuse lack of volatility with stability, ever” is a quote from Nassim Nicolas Taleb that’s seems particularly apt today.

Andrew Lapthorne of SocGen highlighted that low risk markets tend to have a big knock on effect with a “positive feedback mechanism embedded in many risk models”. In other words, the less risk is observed in the market and used as the basis for model inputs, the more risk the quant models allow investors to take! [The impact of quant models and shadow risks from passive investing and machine learning are areas I hope to explore further in a future post.]

One risk that has the potential to spoil the party in 2018 is the planned phased normalisation of monetary policy around the world after the great experimentations of recent years. The market is currently assuming that Central Banks will guarantee that Goldilocks will remain unfrazzled as they deftly steer the ship back to normality. A global “Goldilocks put” if I could plagiarize “the Greenspan put”! Or a steady move away from the existing policy that no greater an economic brain than Donald Trump summarized as being: “they’re keeping the rates down so that everything else doesn’t go down”.

The problem for Central Banks is that if inflation stays muted in the short-term and monetary policy remains loose than the asset bubbles will reach unsustainable levels and require pricking. Or alternatively, any attempt at monetary policy normalization may dramatically show how Central Banks have become the primary providers of liquidity in capital markets and that even modest tightening could result in dangerously imbalances within the now structurally dependent system.

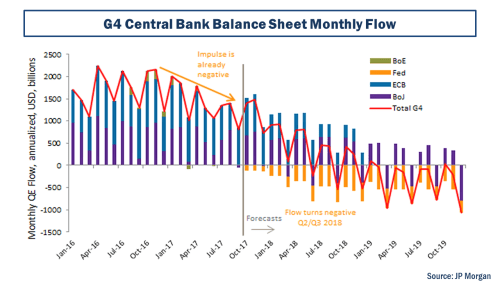

Many analysts (and the number is surprising large) have been warning for some time about the impact of QE flows tightening in 2018. These warnings have been totally ignored by the market, as the lack of volatility illustrates. For example, in June 2017, Citi’s Matt King projected future Central Bank liquidity flows and warned that a “significant unbalancing is coming“. In November 2017, Deutsche Bank’s Alan Ruskin commented that “2018 will see the world’s most important Central Bank balance sheets shift from a 12 month expansion of more than $2 trillion, to a broadly flat position by the end of 2018, assuming the Fed and ECB act according to expectations”. The projections Deutsche Bank produced are below.

click to enlarge

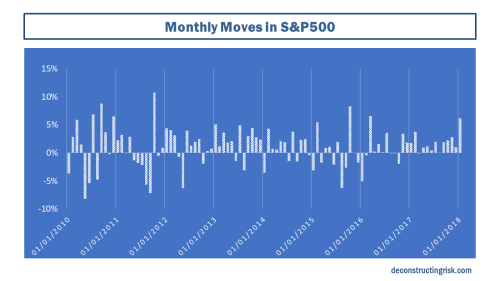

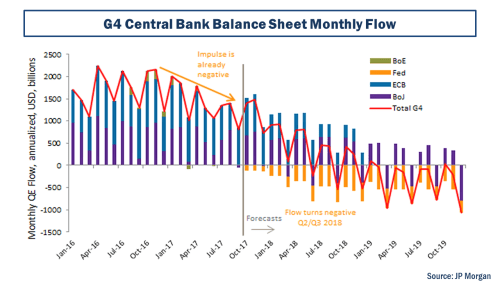

Andrew Norelli of JP Morgan Asset Management in a piece called “Stock, Flow or Impulse?” stated that “It’s still central bank balance sheets, and specifically the flow of global quantitative easing (QE) that is maintaining the buoyancy in financial asset prices”. JP Morgan’s projections of the top 4 developed countries are below.

click to enlarge

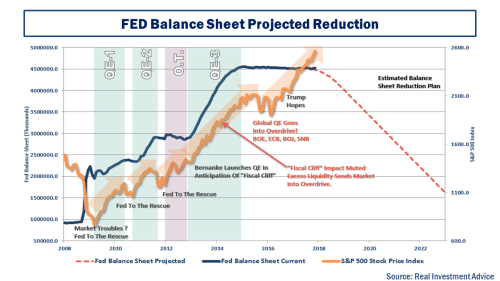

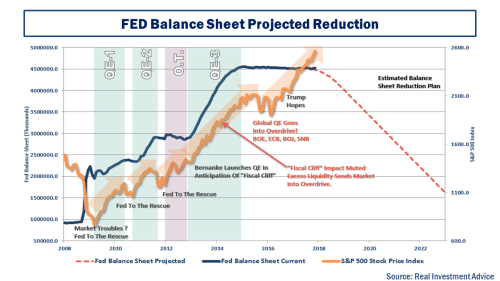

Lance Roberts of RealInvestmentAdvice.com produced an interesting graph specifically relating to the Fed’s balance sheet, as below. Caution should be taken with any upward trending metric when compared to the S&P500 in recent years!

click to enlarge

Of course, we have been at pre-taper junctions many times before and every previous jitter has been met with soothing words from Central Banks and more liquidity creation. This time though it feels different. It has to be different. Or Central Bankers risk been viewed as emperors without cloths.

The views of commentators differ widely on this topic. Most of the business media talking heads are wildly positive (as they always are) on the Goldilocks status quo. John Mauldin of MauldinEconomics.com believes the number one risk factor in the US is Fed overreach and too much tightening. Bank of America Merrill Lynch chief investment strategist Michael Hartnett, fears a 1987/1994/1998-style flash crash within the next three months caused by a withdrawal of central bank support as interest rates rise.

Christopher Cole of Artemis Capital Management, in a wonderful report called “Volatility and the Alchemy of Risk”, pulls no punches about the impact of global central banks having pumped $15 trillion in cheap money stimulus into capital markets since 2009. Cole comments that “amid this mania for investment, the stock market has begun self-cannibalizing” and draws upon the image of the ouroboros, an ancient Greek symbol of a snake eating its own tail. Cole estimates that 40% of EPS growth and 30% of US equity gains since 2009 have been as a direct result of the financial engineering use of stock buy backs. Higher interest rates, according to Cole, will be needed to combat the higher inflation that will result from this liquidity bonanza and will cut off the supply for the annual $800 billion of share buybacks. Cole also points to the impact on the high yield corporate debt market and the overall impact on corporate defaults.

Another interesting report, from a specific investment strategy perspective, is Fasanara Capital’s Francesco Filia and the cheerfully entitled “Fragile Markets On The Edge of Chaos”. As economies transition from peak QE to quantitative tightening, Filia “expect markets to face their first real crash test in 10 years” and that “only then will we know what is real and what is not in today’s markets, only then will we be able to assess how sustainable is the global synchronized GDP growth spurred by global synchronized monetary printing”. I like the graphic below from the report.

click to enlarge

I found the reaction to the Trump’s administration misstep on dollar strength interesting this week. Aditya Bhave and Ethan Harris, economists at Bank of America, said of the episode that “the Fed will see the weak dollar as a sign of easy financial conditions and a green light to keep tightening monetary policy”. ECB President Mario Draghi was not happy about the weak dollar statement as that would complicate Europe’s quantitative tightening plans. It was also interesting to hear Benoit Coeure, a hawkish member ECB executive board, saying this week that “it’s happening at different paces across the region, but we are moving to the point where we see wages going up”.

I think many of the Central Banks in developed countries are running out of wriggle room and the markets have yet to fully digest that reality. I fear that Goldilocks is about to get frazzled.