Fintech is a much hyped term currently that covers an array of new financial technologies. It includes technology providers of financial services, new payment technologies, mobile money and currencies like bitcoin, robo-advisers, crowd funding and peer to peer (P2P) lending. Blockchain is another technology that is being hyped with multiple potential uses. I posted briefly on the growth in P2P lending and crowd-funding before (here and here) and it’s the former that is primarily the focus of this post.

Citigroup recently released an interesting report on the digital disruption impact of fintech on banking which covers many of the topics above. The report claims that $19 billion has been invested in fintech firms in 2015, with the majority focussed in the payments area. In terms of the new entrants into the provision of credit space, the report highlights that over 70% of fintech investments to date have being in the personal and SME business segments.

In the US, Lending Club and Prosper are two of the oldest and more established firms in the marketplace lending sector with a focus on consumer lending. Although each are growing rapidly and have originated loans in the multiple of billions in 2015, the firms have been having a rough time of late with rates being increased to counter poor credit trends. Public firms have suffered from the overall negative sentiment on banks in this low/negative interest rate environment. Lending Club, which went public in late 2014, is down about 70% since then whilst Prosper went for institutional investment instead of an IPO last year. In fact, the P2P element of the model has been usurped as most of the investors are now institutional yield seekers such as hedge funds, insurers and increasingly traditional banks. JP Morgan invested heavily in another US firm called OnDeck, an online lending platform for small businesses, late in 2015. As a result, marketplace lending is now the preferred term for the P2P lenders as the “peer” element has faded.

Just like other disruptive models in the technology age, eBay and Airbnb are examples, initially these models promised a future different from the past, the so called democratization of technology impact, but have now started to resemble new technology enabled distribution platforms with capital provided by already established players in their sectors. Time and time again, digital disruption has eroded distribution costs across many industries. The graphic from the Citi report below on digital disruption impact of different industries is interesting.

Marketplace lending is still small relative to traditional banking and only accounts for less than 1% of loans outstanding in the UK and the US (and even in China where its growth has been the most impressive at approx 3% of retail loans). Despite its tiny size, as with any new financial innovation, concerns are ever-present about the consequences of change for traditional markets.

Prosper had to radically change its underwriting process after a shaky start. One of their executives is recently quoted as saying that they “will soon be on our sixth risk model”. Marrying new technology with quality credit underwriting expertise (ignoring the differing cultures of each discipline) is a key challenge for these fledging upstarts. An executive in Kreditech, a German start-up, claimed that they are “a tech company who happens to be doing lending”. Critics point to the development of the sector in a benign default environment with low interest rates where borrowers can easily refinance and the churning of loans is prevalent. Adair Turner, the ex FSA regulator, recently stirred up the new industry with the widely reported comment that “the losses which will emerge from peer-to-peer lending over the next five to 10 years will make the bankers look like lending geniuses”. A split of the 2014 loan portfolio of Lending Club in the Citi report as below illustrates the concern.

Another executive from the US firm SoFi, focused on student loans, claims that the industry is well aware of the limitations that credit underwriting solely driven by technology imbues with the comment that “my daughter could come up with an underwriting model based upon which band you like and it would work fine right now”. Some of the newer technology firms make grand claims involving superior analytics which, combined with technologies like behavioural economics and machine learning, they contend will be able to sniff out superior credit risks.

The real disruptive impact that may occur is that these newer technology driven firms will, as Antony Jenkins the former CEO of Barclays commented, “compel banks to significantly automate their business”. The Citigroup report has interesting statistics on the traditional banking model, as per the graphs below. 60% to 70% of employees in retail banking, the largest profit segment for European and US banks, are supposedly doing manual processing which can be replaced by automation.

Another factor driving the need to automate the banks is the cyber security weaknesses in patching multiple legacy systems together. According to the Citigroup report, “the US banks on average appear to be about 5 years behind Europe who are in turn about a decade behind Nordic banks”. Within Europe, it is interesting to look at the trends in bank employee figures in the largest markets, as per the graph below. France in particular looks to be out of step with other countries.

Regulators are also starting to pay attention. Just this week, after a number of scams involving online lenders, the Chinese central bank has instigated a crack down and constituted a multi-agency task force. In the US, there could be a case heard by the Supreme Court which may create significant issues for many online lenders. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency recently issued a white paper to solicit industry views on how such new business models should be regulated. John Williams of the San Francisco Federal Reserve recently gave a speech at a recent marketplace lending conference which included the lucid point that “as a matter of principle, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it should be regulated like a duck”.

In the UK, regulators have taken a gentler approach whereby the new lending business models apply for Financial Conduct Authority authorisation under the 36H regulations, which are less stringent than the regimes which apply to more established activities, such as collective investment schemes. The FCA also launched “Project Innovate” last year where new businesses work together with the FCA on their products in a sandbox environment.

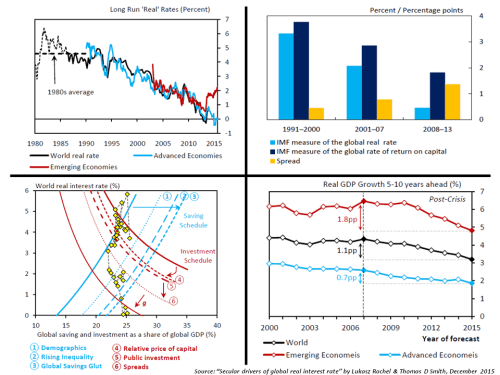

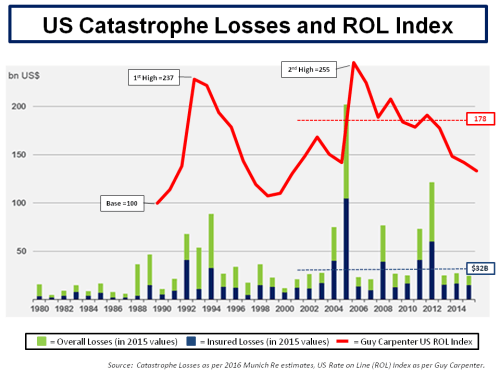

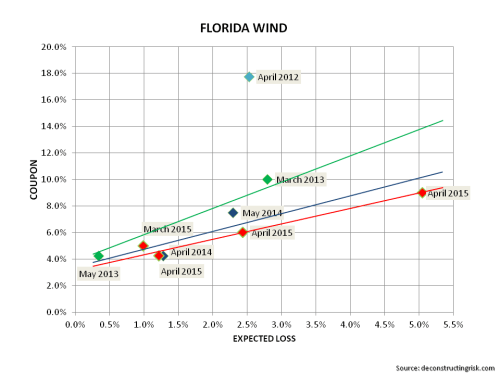

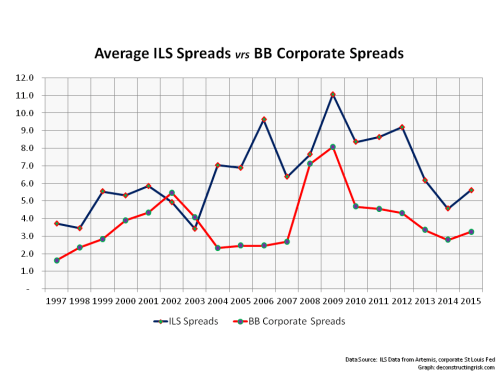

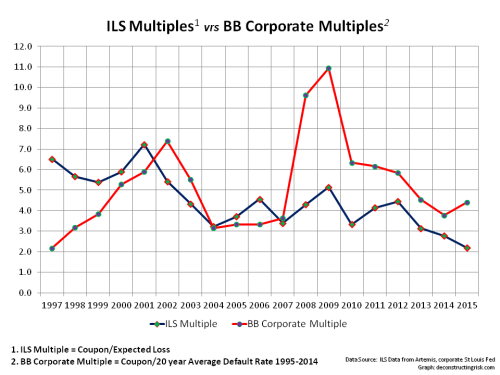

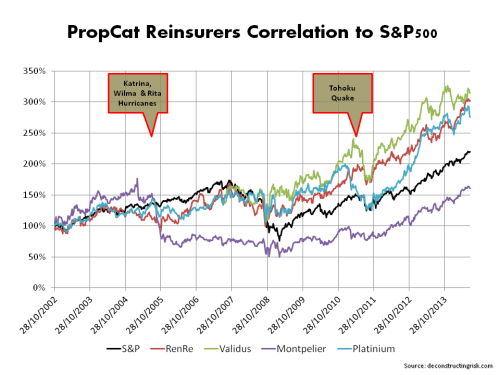

Back in 2013, I asked the question whether financial innovation always ended in lower risk premia in this post. In the reinsurance sector, the answer to that question is yes in relation to insurance linked securities (ILS) as this recent post on current pricing shows. It has occurred to me that the new collateralised ILS structures are not dissimilar in methodology to the 100% reserve banks, under the so-called Chicago plan, which economists such as Irving Fisher, Henry Simons and Milton Friedman proposed in the 1930s and 1940s. I have previously posted on my difficulty in understanding how the fully collaterised insurance model can possibly accept lower risk premia than the traditional “fractional” business models of traditional insurers (as per this post). The reduced costs of the ILS model or the uncorrelated diversification for investors cannot fully compensate for the higher capital required, in my view. I suspect that the reason is hiding behind a dilution of underwriting standards and/or leverage being used by investors to juice their returns. ILS capital is now estimated to make up 12% of overall reinsurance capital and its influence on pricing across the sector has been considerable. In Part 2 of this post, I will look into some of the newer marketplace insurance models being developed (it also needs a slick acronym – InsurTech).

Marketplace lending is based upon the same fully capitalized idea as ILS and 100% reserve banks. As can be seen by the Citigroup exhibits, there is plenty of room to compete with the existing banks on costs although nobody, not yet anyway, is claiming that such models have a lower cost of capital than the fractional reserve banks. It is important not to over exaggerate the impact of new models like marketplace lending on the banking sector given its current immaterial size. The impact of technology on distribution channels and on credit underwriting is likely to be of greater significance.

The indirect impact of financial innovation on underwriting standards prior to the crisis is a lesson that we must learn. To paraphrase an old underwriting adage, we should not let the sweet smell of shiny new technology distract us from the stink of risk, particularly where such risk involves irrational human behaviour. The now infamous IMF report in 2006 which stated that financial innovation had “increased the resilience of the financial system” cannot be forgotten.

I am currently reading a book called “Between Debt and the Devil” by the aforementioned Adair Turner where he argues that private credit creation, if left solely to the free market under our existing frameworks, will overfund secured lending on existing real estate (which my its nature is finite), creating unproductive volatility and financial instability as oversupply meets physical constraints. Turner’s book covers many of the same topics and themes as Martin Wolf’s book (see this post). Turner concludes that we need to embrace policies which actively encourage a less credit intensive economy.

It is interesting to see that the contribution of the financial sector has not reduced significantly since the crisis, as the graph on US GDP mix below illustrates. The financialization of modern society does not seem to have abated much since the crisis. Indeed, the contribution to the value of the S&P500 from the financials has not decreased materially since the crisis either (as can be seen in the graph in this post).

Innovation which makes business more efficient is a feature of the creative destruction capitalist system which has increased productivity and wealth across generations. However, financial innovation which results in changes to the structure of markets, particularly concerning banking and credit creation, has to be carefully considered and monitored. John Kay in a recent FT piece articulated the dangers of our interconnected financial world elegantly, as follow:

“Vertical chains of intermediation, which channel funds directly from savers to the uses of capital, can break without inflicting much collateral damage. When intermediation is predominantly horizontal, with intermediaries mostly trading with each other, any failure cascades through the system.”

When trying to understand the potential impacts of innovations like new technology driven underwriting, I like to go back to an exhibit I created a few years ago trying to illustrate how financial systems have been impacted at times of supposed innovation in the past.

Change is inevitable and advances in technology cannot, nor should they, be restrained. Human behaviour, unfortunately, doesn’t change all that much and therefore how technological advances in the financial sector could impact stability needs to be ever present in our thoughts. That is particularly important today where global economies face such transformational questions over the future of the credit creation and money.