There have been some interesting developments in the US insurance sector on the issue of systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Metlife announced plans to separate some of their US life retail units to avoid the designation whilst shareholder pressure is mounting on AIG to do the same. These events are symptoms of global regulations designed to address the “too big to fail” issue through higher capital requirements. It is interesting however that these regulations are having an impact in the insurance sector rather than the more impactful issue within the banking sector (this may have to do with the situation where the larger banks will retain their SIFI status unless the splits are significant).

The developments also fly in the face of the risk management argument articulated by the insurance industry that diversification is the answer to the ills of failure. This is the case AIG are arguing to counter calls for a breakup. Indeed, the industry uses the diversification of risk in their defences against the sector being deemed of systemic import, as the exhibit below from a report on systemic risk in insurance from an industry group, the Geneva Association, in 2010 illustrates. Although the point is often laboured by the insurance sector (there still remains important correlations between each of the risk types), the graph does make a valid point.

The 1st of January this year marked the introduction of the new Solvency II regulatory regime for insurers in Europe, some 15 years after work begun on the new regime. The new risk based solvency regime allows insurers to use their own internal models to calculate their required capital and to direct their risk management framework. A flurry of internal model approvals by EU regulators were announced in the run-up to the new year, although the amount of approvals was far short of that anticipated in the years running up to January 2016. There will no doubt be some messy teething issues as the new regime is introduced. In a recent post, I highlighted the hoped for increased disclosures from European insurers on their risk profiles which will result from Solvency II. It is interesting that Fitch came out his week and stated that “Solvency II metrics are not comparable between insurers due to their different calculation approaches and will therefore not be a direct driver of ratings” citing issues such as the application of transitional measures and different regulator approaches to internal model approvals.

I have written many times on the dangers of overtly generous diversification benefits (here, here, here, and here are just a few!) and this post continues that theme. A number of the large European insurers have already published details of their internal model calculations in annual reports, investor and analyst presentations. The graphic below shows the results from 3 large insurers and 3 large reinsurers which again illustrate the point on diversification between risk types.

The reinsurers show, as one would expect, the largest diversification benefit between risk types (remember there is also significant diversification benefits assumed within risk types, more on that later) ranging from 35% to 40%. The insurers, depending upon business mix, only show between 20% and 30% diversification across risk types. The impact of tax offsets is also interesting with one reinsurer claiming a further 17% benefit! A caveat on these figures is needed, as Fitch points out; as different firms use differing terminology and methodology (credit risk is a good example of significant differences). I compared the diversification benefits assumed by these firms against what the figure would be using the standard formula correlation matrix and the correlations assuming total independence between the risk types (e.g. square root of the sum of squares), as below.

What can be seen clearly is that many of these firms, using their own internal models, are assuming diversification benefits roughly equal to that between those in the standard formula and those if the risk types were totally independent. I also included the diversification levels if 10% and 25% correlations were added to the correlation matrix in the standard formula. A valid question for these firms by investors is whether they are being overgenerous on their assumed diversification. The closer to total independence they are, the more sceptical I would be!

Assumed diversification within each risk type can also be material. Although I can understand arguments on underwriting risk types given different portfolio mixes, it is hard to understand the levels assumed within market risk, as the graph below on the disclosed figures from two firms show. Its hard for individual firms to argue they have material differing expectations of the interaction between interest rates, spreads, property, FX or equities!

Diversification within the life underwriting risk module can also be significant (e.g. 40% to 50%) particularly where firms write significant mortality and longevity type exposures. Within the non-life underwriting risk module, diversification between the premium, reserving and catastrophe risks also add-up. The correlations in the standard formula on diversification between business classes vary between 25% and 50%.

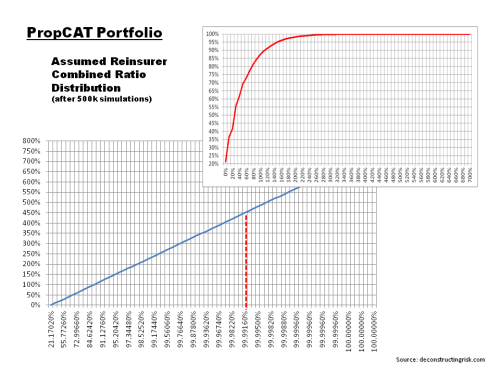

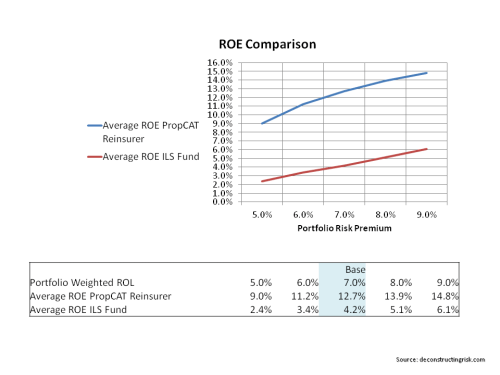

By way of a thought experiment, I constructed a non-life portfolio made up of five business classes (X1 to X5) with varying risk profiles (each class set with a return on equity expectation of between 10% and 12% at a capital level of 1 in 500 or 99.8% confidence level for each), as the graph below shows. Although many aggregate profiles may reflect ROEs of 10% to 12%, in my view, business classes in the current market are likely to have a more skewed profile around that range.

I then aggregated the business classes at varying correlations (simple point correlations in the random variable generator before the imposition of the differing distributions) and added a net expense load of 5% across the portfolio (bringing the expected combined ratio from 90% to 95% for the portfolio). The different resulting portfolio ROEs for the different correlation levels shows the impact of each assumption, as below.

The experiment shows that a reasonably diverse portfolio that can be expected to produce a risk adjusted ROE of between 14% and 12% (again at a 1 in 500 level)with correlations assumed at between 25% and 50% amongst the underlying business classes. If however, the correlations are between 75% and 100% then the same portfolio is only producing risk adjusted ROEs of between 10% and 4%.

As correlations tend to increase dramatically in stress situations, it highlights the dangers of overtly generous diversification assumptions and for me it illustrates the need to be wary of firms that claim divine diversification.