The insurance sector has been hit by the Brexit fallout on worries about macro-economic impacts; albeit not to the same extend as the banks. Swiss Re has their latest Sigma world insurance report out. The impact of investment returns on the life insurance sector is obvious but it is interesting to see the contribution from investment income on the profitability of the aggregate of the eight largest markets in the non-life insurance sector, as per the graph from the report below.

The insurance sector faces a number of challenges as a recent FT article pointed out. The reinsurance sector also faces challenges, not least of which is a competitive pricing environment and the destabilising influx of new yield seeking capital through new innovations in the insurance linked securities (ILS) market. I have posted my views on the ILS sector many times (more recently here) and in this post I offer more similar thoughts. It is interesting to compare the ROEs in the Sigma report from the non-life insurance sector against those from the reinsurance sector (with the ROEs since 2005 coming from the Guy Carpenter composite index), as per the graph below.

The graph is not exactly comparing like with like (e.g. non-life insurance versus composite reinsurance) but it gives the general idea of higher but more volatile ROEs in the reinsurance side compared to more stable but lower ROEs on the direct insurance side. The average since 1999 for insurance is 7% and 9% for reinsurance, with standard deviations of 3.6% and 4.6% respectively. It also confirms that ROEs are under pressure for both sectors and as capital markets continue to siphon off volatile excess catastrophe exposed business, the ROEs of the more proportional traditional reinsurance sector are converging on those of their direct brethren, although a differential will always exist given the differing business models.

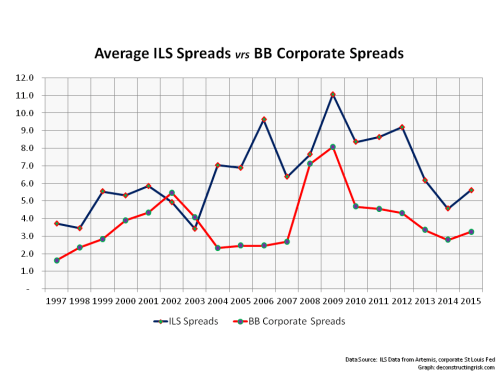

It is important to note that these ROEs are returns on equity held by traditional insurers and reinsurers, the majority of which are highly rated by external agencies, who hold a small fraction of their total exposure (if measured as the sum of the policy limits issued) as capital. For example, the new European solvency framework, Solvency II, requires capital at a 1 in 200 level and it is generally assumed to be akin to a financial strength rating of BB or BBB, depending upon a firm’s risk profile.

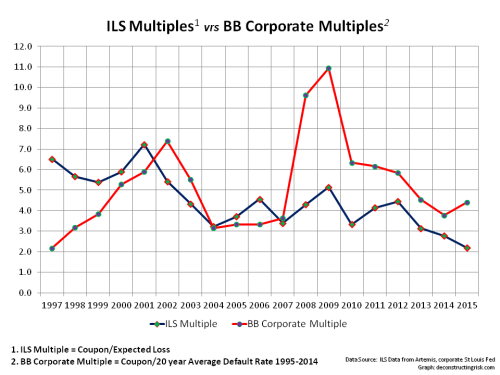

As I argued previously (more recently in this post), these (re)insurers are akin to fractional reserve banks and I still struggle to understand how ILS structures, which are 100% collaterised, can offer their investors such an attractive return given their fully funded “capital” level in the ROE calculation. The industry argument is that investors have a lower cost of capital due to the uncorrelated nature of the pure insurance risk present in ILS.

My suspicion is that the lower cost of capital assigned by investors is reflective of a lack of understanding of the uncertainties surrounding the risks they are taking on and an over-reliance on modelling which does not fully consider the uncertainties. My fear is that capital is been leveraged or risks are been arbitraged through over-generous retrocession deals passing on under-priced risk to naive capital newcomers.

The accelerating growth in the so-called alternative capital in insurance is shown in the graph below from Aon Benfield, with growth in the private collaterised reinsurance being particularly strong in the last four years (now overshadowing the public CAT bond market). ILS funds, managed by professional asset manager specialists, are largely behind the growth in private collaterised deals with assets under management growing from $20 billion in 2012 to over $50 billion today. Private collaterised deals are usually lower down the reinsurance tower (e.g. attach at lower loss levels) and as such offer higher premiums (as a percentage of limits, aka rate on line or ROL) for the increased exposure to loss. On a risk adjusted basis, these don’t necessarily offer higher ROEs than higher attaching/lower risk CAT bonds.

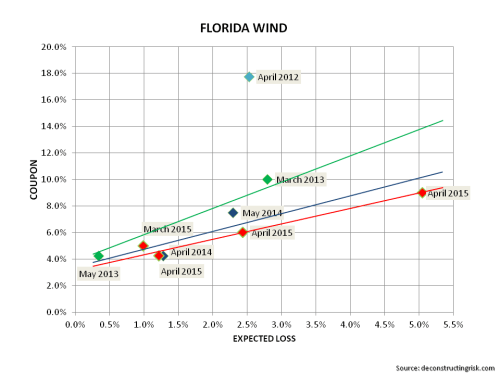

Property catastrophe pricing has been under particular pressure in the past few years due to the lack of significant insured catastrophe losses. In a previous post, I crudely estimate CAT pricing to be 25% below its technical rate. Willis Re is the first of the brokers to have its mid-year renewal report out. In it, Willis said that ILS funds “were more aggressive on pricing during the second quarter as spreads declined for liquid reinsurance investments”. I also find it interesting that the collaterised ILW volumes have ticked up recently. Pricing and lax terms and conditions in the retrocession sector are historically a sign that discipline is breaking down. Asset managers in the ILS space must be under pressure in maintaining their high fees in a reduced CAT risk premia environment and this pressure is likely to be contributing to the potential for market indiscipline.

I therefore find the graph below very telling. I used the figures from Lane Financial (see here) for the annual total return figures from CAT bonds, which closely match those of the Swiss Re Total Return Index. For the ILS fund returns I used the figures from the Eurekahedge ILS Advisors Index which I adjusted to take out the not unconsiderable typical ILS fund management fees. The 2016 figures are annualized based upon published year to date figures (and obviously assume no major losses).

The graph shows that ILS fund returns have broken with historical patterns and diverged away from those of CAT bonds as the prevalence in private collaterised deals has grown in recent years. In other words, ILS funds have moved to higher rate on line business, which is by definition higher risk, as they push to service the larger level of assets under management. The question is therefore do the investors really understand the significance of this change? Have they adjusted their cost of capital to reflect the increased risk? Or are some ILS funds representing the higher returns as their ability to get higher returns at the same risk level (against the trend of everybody else in the industry in a softening market)?

Innovation is to be encouraged and a necessary part of progress. Innovation dependent on the naivety of new investors however does not end well.

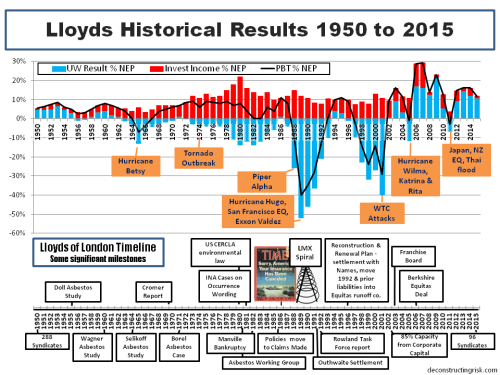

I can’t but help think of Michael Wade’s comment in 2009 about the commonality between the financial crisis and problems at Lloyds of London (see this post on lessons from Lloyds) when he said that “the consequence with the excess capital was that underlying risks could be underpriced as they were being passed on”. My advice to ILS investors is the next time they are getting a sales pitch with promises of returns that sound too good, look around the room, and ask yourself who is the greater fool here….