Insurance linked securities (ILS) are now well established in the insurance industry. ILS as an asset class offer, according to its many fans, the benefits of diversification and low correlation to other asset classes whilst offering a stable and attractive risk/reward return. The impact of the new capital on the traditional market has been profound and wide ranging (and a much posted upon topic in this blog – here, here & here for example).

ILS fund managers maintained an “aggressive posture” on price at the recent April renewals according to Willis Re as ILS capacity continues to demonstrate its cost of capital advantage. ILS fund managers are also looking to diversify, moving beyond pure short tail risks and looking at new previously uninsured or underinsured exposures, as well as looking to move their capital along the value-chain by sourcing primary risk more directly and in bulk.

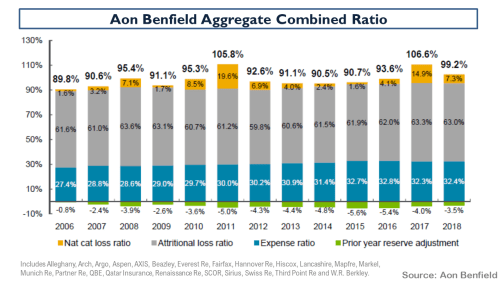

An industry stalwart, John Kavanagh of Willis Re, commented that “with results on many diversifying non-catastrophe classes now marginal, there is greater pressure on reinsurers to address the pricing in these classes” and that “many reinsurers remain prepared to let their top line revenue growth stall and are opting to return excess capital to their shareholders”. The softening reinsurance market cycle is now in its fifth year and S&P estimates that “even assuming continued favourable prior-year reserve releases and benign natural catastrophe losses, we anticipate that reinsurers will barely cover their cost of capital over the next two years”.

Rather than fight the new capital on price, some traditional (re)insurers are, according to Brandan Holmes of Moody’s, “deploying third-party capital in their own capital structures in an effort to lower their blended cost of capital” and are deriving, according to Aon Benfield, “significant benefits from their ability to leverage alternative capital”. One can only fight cheap capital for so long, at some stage you just arbitrage against it (sound familiar!).

A.M. Best recently stated that “more collateralised reinsurance programs covering nonpeak exposures are ceded to the capital markets”. The precipitous growth in the private transacted collateralised reinsurance subsector can be seen in the graph from Aon below.

click to enlarge

Nick Frankland of Guy Carpenter commented that “the capital landscape is ever-changing” and that “such capital diversity also elevates the position of the broker”. Some argue that the all-powerful role of the dominant brokers is exacerbating market softness. These brokers would counterargue that they are simply fulfilling their role in an efficient market, matching buyers and sellers. As Frankland puts it, brokers are “in the strongest position to provide access to all forms of capital and so secure the more beneficial rates and terms and conditions”. Dominic Christian of Aon Benfield commented last year that “to some extent alternative sources of capital are already, and have already uberized insurance and reinsurance, by bringing increased sources of supply”.

Perhaps alone amongst industry participants, Weston Hicks of Alleghany, has questioned the golden goose of cheap ILS capital stating that “some new business models that separate the underwriting decision from the capital provider/risk bearer are, in our view, problematic because of a misalignment of incentives”. Such concerns are batted aside as old fashioned in this new world of endless possibilities. Frighteningly, John Seo of ILS fund manager Fermat Capital, suggests that “for every dollar of money that you see in the market right now, I think there is roughly 10 dollars on the sidelines waiting to come in if the market hardens”.

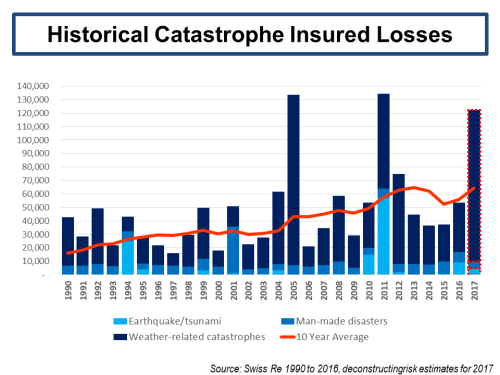

As an indicator of current ILS pricing, the historical market spread over expected losses in the public CAT bond market can be seen in the exhibit below with data sourced from Lane Financial. It is interesting to note that the average expected loss is increasing indicating CAT bonds are moving down the risk towers towards more working layer coverages.

click to enlarge

In a previous post, I argued that returns from an ILS fund index, with the net returns judgementally adjusted to get to comparable figures gross of management fees, were diverging against those from a pure CAT bond index. I argued that this divergence may illustrate that the ILS funds with exposure to the private collateralised reinsurance sector may be taking on higher risk exposures to pump returns (or may be passing risks amongst themselves in an embryonic spiral) and that ILS investors should be careful they understand the detail behind the risk profiles of the ILS funds they invest in.

Well, the final 2016 figures, as per the graph below, show that the returns in my analysis have in fact converged rather than diverged. On the face of it, this rubbishes my argument and I have to take that criticism on. Stubbornly, I could counter-argue that the ILS data used in the comparison may not reflect the returns of ILS funds with large exposure to collateralised reinsurance deals. Absent actual catastrophic events testing the range of current fund models, better data sources are needed to argue the point further.

click to enlarge

In their annual review of 2016, Lane Financial have an interesting piece on reducing transparency across both the public and private ILS sector. They characterise the private collateralised reinsurance sector as akin to a dark pool compared to the public CAT bond market which they likened to a lit exchange. Decreased transparency across the ILS sector “should send up warning flags” for all market participants as it makes calculating Net Asset Valuations (NAV) with monthly or quarterly frequency more difficult. They argue that the increased use of a relatively smaller public CAT bond market for pricing points across the ILS sector, the less credible is the overall valuation. This is another way of expressing my concern that the collateralised reinsurance market could be destabilising as it is hidden (and unregulated).

In the past, as per this post, I have questioned how the fully funded ILS market can claim to have a lower cost of capital against rated reinsurers who only have to hold capital against a percentage of their exposed limit, akin to fractional banking (see this post for more on that topic). The response is always down to the uncorrelated nature of ILS to other asset classes and therefore its attraction to investors such as pension funds who can apply a low cost of capital to the investment due to its uncorrelated and diversifying portfolio benefits. Market sponsors of ILS often use graphs such as the one below from the latest Swiss Re report to extoll the benefits of the asset class.

click to enlarge

A similar exhibit, this time from a Lombard Odier brochure, from 2016 shows ILS in an even more favourable light!

click to enlarge

As anybody who has looked through any fund marketing metrics knows, performance comparisons with other investment strategies are fraught with bias and generally postdictive. The period over which the comparison is made and the exact indices chosen (look at the differing equity indices used in the comparisons above) can make material differences. Also, the size and liquidity of a market is important, a point which may negate any reliance on ILS returns prior to 2007 for example.

I thought an interesting exercise would be to compare actual historical ILS returns, as represented by the Swiss Re Global Cat Bond Total Return Index, against total returns (i.e. share price annual change plus dividends paid in year) from equity investment in reinsurers across different time periods. The most applicable business model for comparison would be pure property catastrophe reinsurers but unfortunately there are not many of them left.

I have chosen RenRe (RNR) and Validus (VR), from 2007, as representatives of the pure property cat business model, although both have diversified their portfolios away from pure short tail business in recent years. I also selected three of the biggest European reinsurers – Munch Re, Swiss Re and Hannover Re – all of which are large diverse composite reinsurers. Finally, I constructed a US$ portfolio using equal shares of each of the five firms mentioned above (RenRe represents 40% of the portfolio until 2007 when Validus went public) with the € and CHF shares converted at each year end into dollars.

The construction of any such portfolio is postdictive and likely suffers from multiple biases. Selecting successful firms like RenRe and Validus could validly be criticised under survival bias. To counter such criticism, I would point out that the inclusion of the European reinsurers is a considerable historic drag on returns given their diverse composite footprint (and associated correlation to the market) and the exclusion of any specialist CAT firm that has been bought out in recent years, generally at a good premium, also drags down returns.

The comparison over the past 15 years, see graph below, shows that Munich and Swiss struggle to get over their losses from 2002 and 2003 and during the financial crisis. Hannover is the clear winner amongst the Europeans. The strong performance of Hannover, RenRe and Validus mean that the US$ portfolio matches the CAT bond performance after the first 10 years, albeit on a more volatile basis, before moving ahead on a cumulative basis in the last 5 years. The 15-year cumulative return is 217% for the CAT bond index and 377% return for the US$ equity portfolio.

click to enlarge

The comparison over the past 10 years, see graph below, is intriguing. Except for Validus, the CAT bond index beats all other firms and the US$ portfolio for non-volatile returns hands down in the first 5 years. Hannover, Validus and the portfolio each make a strong comeback in the most recent 5 years. The 10-year cumulative return is 125% for the CAT bond index and 189% return for the US$ equity portfolio.

click to enlarge

The comparison over the past 5 years, see graph below, shows that all firms and the portfolio handily beats the CAT bond index. Due to an absence in large loss activity over the recent past and much more shareholder friendly actions by all reinsurers, the equity returns have been steady and non-volatile. The 5-year cumulative return is 46% for the CAT bond index and 122% return for the US$ equity portfolio.

click to enlarge

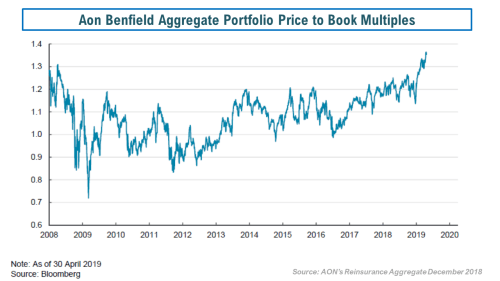

Overall then, ILS may offer less volatile and uncorrelated returns but I would personally prefer the, often lumpier, historical equity returns from a selected portfolio of top reinsurers in my pension pot (we all could have both in our pension funds!). Then again, the influx of new capital into ILS has put the future viability of the traditional reinsurance business models into question so future equity returns from the sector may not be too rosy.

At the end of the day, the bottom line is whether current market risk premia is adequate, irrespective of being supplied by ILS fund managers or traditional reinsurers. Based upon what I see, I have grave misgivings about current market pricing and therefore have no financial exposure, ILS or equity or otherwise, to the market at present.

Additional Comment, 29th April 2017: The ILS website Artemis.bm had an interesting piece on comments from Torsten Jeworrek of Munich Re during their March conference call. The applicable comment is as follows:

“And now I give you another example, which is not innovation per se or not digitalization, but you know that more and more alternative capital came into the insurance industry over the last years; hedge funds, pension refunds, participating particularly in the cat business and as a trend that not all of the limits they provide, cat limits are fully collateralized anymore. That means there are 10 scenarios; hurricane, earthquake, [indiscernible], and so on; which are put together, but not 10 times the limit is collateralized, let’s say only 4 times, 5 times.

That means these hedge funds and pension funds so to speak in the future if they don’t have to provide full 100% collateralized for all the limits they provide, they need a certain credit risk for the buyer. The more they entertain, the more there’s a likelihood that this reinsurance can also fail. The question is how far will that go and this kind of not fully collateralized reinsurance, will that be then accepted as a reinsurance by the regulator or will that be penalized at a certain time otherwise we don’t have level playing field anymore, which means the traditional reinsurer who was strongly monitored and regulated and also reported as really expensive and a burden for our industry and for us and on the other hand, you have very lean pension and hedge funds who even don’t have to provide the same amount of capital for the same risk.”